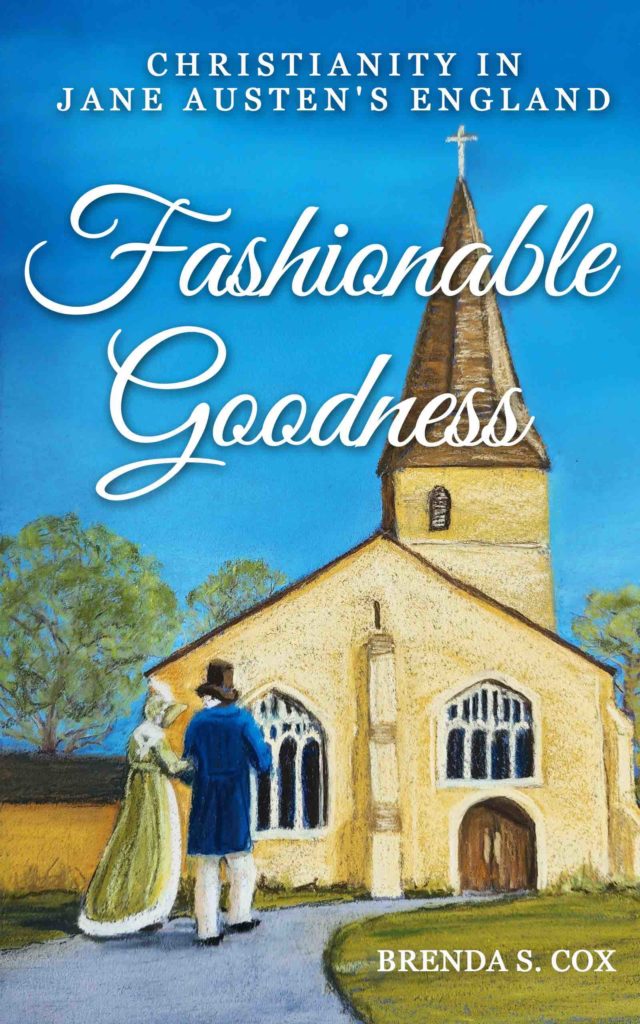

Here at Austen Variations, WE’RE ALL ABOUT FICTION, as you know. But occasionally one of us will feature a non-fiction book we think will be of interest to our readers. So today, I want to do just that! I want tell you about a fascinating book that I had the privilege of, in my own small way, helping to bring to publication. It’s by Brenda Cox, and it’s called Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. So why will you want to read it? Here’s what the publisher has to say about the book:

Here at Austen Variations, WE’RE ALL ABOUT FICTION, as you know. But occasionally one of us will feature a non-fiction book we think will be of interest to our readers. So today, I want to do just that! I want tell you about a fascinating book that I had the privilege of, in my own small way, helping to bring to publication. It’s by Brenda Cox, and it’s called Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England. So why will you want to read it? Here’s what the publisher has to say about the book:

Jane Austen transports us to a world of elegance and upheaval, at the heart of which was her Anglican Church. Without understanding it, we miss much of the story. We’re left wondering…

- Why could the rector Mr. Collins afford to marry a poor woman, whereas a vicar like Mr. Elton could not?

- What conflicting religious duties led Elizabeth Bennet to turn down two very different proposals?

- Why did Austen’s early readers (unlike most today) adore Mansfield Park’s Fanny Price?

- What part did people of color, like Miss Lambe of Sanditon, play in English society?

- How did the Church impact people’s lives and the world?

Explore these questions and so much more in Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England.

“Brenda Cox’s scholarly, detailed work is a triumph. Easily read, helpful and accurate… Its many insights will enrich readers’ understanding and appreciation of Jane Austen’s novels and her life as a devout Christian.”—The Revd. Canon Michael Kenning, Vice-Chairman of the Jane Austen Society and former rector of Steventon

“Finally! Fashionable Goodness is the Jane Austen reference book that’s been missing from the bookshelves of every Austen fan and scholar.” — Rachel Dodge, bestselling author of Praying with Jane

To most of us, the workings of the nineteenth century Anglican Church are a mystery. And yet they were absolutely central to Jane Austen’s world, especially as a clergyman’s daughter. As it says above, without knowing something about her church and her personal faith, we miss a lot when we read Jane Austen’s stories. To quote Brenda, “The more facets of Austen’s era we understand, the better we can appreciate her novels.” So here’s an opportunity to be more than a surface reader, to delve a bit deeper and discover more about Austen – the woman and her writings.

To most of us, the workings of the nineteenth century Anglican Church are a mystery. And yet they were absolutely central to Jane Austen’s world, especially as a clergyman’s daughter. As it says above, without knowing something about her church and her personal faith, we miss a lot when we read Jane Austen’s stories. To quote Brenda, “The more facets of Austen’s era we understand, the better we can appreciate her novels.” So here’s an opportunity to be more than a surface reader, to delve a bit deeper and discover more about Austen – the woman and her writings.

I first became involved with Fashionable Goodness when Brenda (whom I finally met in person at the recent AGM in Victoria!) asked me to beta read the book. Then much later, she contracted me to create the artwork for the cover! I only wish I had had the chance to read Brenda’s book before I began writing JAFF. I would have had more insight into the Jane Austen novels my books are based on and been able to put in more of those accurate period details that help to solidly anchor a story in the past.

In fact, that’s how Brenda got started on this ambitious project in the first place! She wanted to write a Sense and Sensibility novel, including characters of active faith. But she couldn’t find a good source for the information she needed about the Church and the practice of Christianity in early nineteenth century England. Ultimately, she decided to write that source book herself.

St. Nicholas Church, Chawton

Fashionable Goodness is so packed with valuable material that it’s hard to adequately summarize here. The first third of the book – Jane Austen’s Church of England – basically explains who’s who and how things worked. Part Two is entitled Challenges to Jane Austen’s Church of England. It covers some of the church’s weaknesses and efforts to overcome them. It also includes the situation of dissenters, people of color, and others outside the mainstream faith at the time. Part Three – Outreach and Legacy of the Church in Austen’s England – tells about a few of the social and religious leaders of the day (John Newton, William Cowper, William Wilberforce, Hannah More) and efforts to eradicate some of the worst of social ills – how this significantly changed the world. Whenever possible, the author ties every issue back to Jane Austen herself and/or incidents in her stories, giving us a familiar frame of reference for what we’re learning.

One thing that grabbed my interest in particular was the illuminating explanation of some key words in Austen’s stories – words her contemporaries would have understood but that were intended to convey more or different meanings than we are likely to give them credit for today. Language changes over time, impairing our ability to correctly understand things written long ago. I had run into that issue before myself with words like intercourse, saloon, housekeeper, intimate, and wonderful. (See my post: Them Are Stumbling Words) Brenda points out some words that have easily-overlooked faith implications. Quoting from a recent interview:

I spoke at this year’s JASNA AGM about the spiritual messages in Sense and Sensibility. I see S&S as a story contrasting the selfishness of characters like Willoughby with the self-denial, or selflessness, of characters like Elinor. Austen used words like “exertion” that had religious implications at the time. We easily miss those today, and I’ve enjoyed exploring what Austen was saying with those words.

Austen always promoted moral behavior. But she didn’t do it by preaching and telling people what to do. Instead, she showed examples, both positive and negative. Readers of Pride and Prejudice, for instance, might learn to avoid judging and ridiculing other people. We might instead want to be more like Jane Bennet, assuming the best of others until the worst is clearly proven. (This was a religious virtue called “candour” in Austen’s time).

Follow this link to Brenda’s website/blog, where you will find explanations for the religious overtones of these words and others (duty, principle, serious). Or you can, of course, look for that section in the book! Even the word “manners” means a lot more than polite behavior at the table or on the dance floor.

Manners: Behavior, the way people act based on their religious or moral principles (good or bad). Examples: “The manners I speak of, might rather be called conduct, perhaps, the result of good principles” – Edmund Bertram, Mansfield Park, ch 9. “But in the central part of England there was surely some security for the existence even of a wife not beloved, in the laws of the land, and the manners of the age.” – Northanger Abbey, ch. 25 (Fashionable Goodness, ch. 3)

There’s so much more that I could tell you if time and space allowed. Let me just say that if you are a writer of Regency fiction, a history buff, or simply a Jane Austen fan who wants to more fully understand and appreciate her work, this book should be on your reading list. Why did Brenda call it Fashionable Goodness: Christianity in Jane Austen’s England? I’ll leave you with her answer to that question:

During Austen’s time, it was fashionable to attend church and pretend to be “good.” But the Prince Regent and others had made immorality more fashionable than morality. William Wilberforce was probably the most influential Christian of Austen’s England. One of his goals was to reform the “manners” of England. Edmund Bertram explains that “manners” meant behavior, how people acted based on their religious principles. Wilberforce and many others promoted moral behavior–trying to make “goodness” fashionable in England. And amazingly, they succeeded! My book shows what “fashionable goodness” looked like in Regency England and what it came to look like by the Victorian era. And it explains how committed Christians like Wilberforce, Hannah More, and others brought that about. I think that Austen was part of that sweeping change, through her novels promoting moral behavior by example.

Fashionable Goodness is now available in paperback and Kindle versions around the world. Purchase it at Jane Austen Books or Amazon (International link: Amazon)

About the Author: Brenda S. Cox, who has long loved Jane Austen, spent years researching Fashionable Goodness in America and England. A popular speaker at Jane Austen Society of North America meetings, she writes for their academic journal and the website Jane Austen’s World, as well as her own Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.

About the Author: Brenda S. Cox, who has long loved Jane Austen, spent years researching Fashionable Goodness in America and England. A popular speaker at Jane Austen Society of North America meetings, she writes for their academic journal and the website Jane Austen’s World, as well as her own Faith, Science, Joy, and Jane Austen.

11 comments

Skip to comment form

Brenda, congratulations on your new book, and Shannon, thanks for bringing it to our attention! I, too, wish I had been able to read this book before writing my own Sense and Sensibility variation. I thought often (and read a little) about the church, given Edward’s role, but I’m sure I didn’t capture the nuance that Brenda’s book surely brings to light. I’ll have to check it out soon! Fascinating work, and thank you so much for sharing it with us, Brenda.

Author

Glad you enjoyed the post, Christina! Yes, writing remotely (200 years distant and on a different continent), there’s a lot we don’t know and understand. Brenda has really opened this mysterious corner of Jane Austen’s world to us. Thanks for your comment!

Jane Austen was no hypocrite, and she was had keen insight. She recognised this by allowing that the Church and religion as a whole was part of society not society itself. That one can represent something and behave in the opposite. One can go to church (or be destined for it) and live a life divorced from it. If Jane Austen alluding to that is an example of “active faith” then I totally agree. In a way, Austen’s books are a rejection of that Machiavellian thought, of that aspect that pervaded the elite society at the time, and still does today- that “there is nothing more important than appearing to be religious”. I am more interested in how that “active faith” shaped the class distinctions and class discriminations and of Austen’s rejection of a lot of that in her writing as well. As for her clergymen, she shows the gamut of them and how well she can recognise hypocrisy in the Anglican Church, all except one of her books had one. Tilney perhaps was the best church representative, Persuasion, one would argue, didn’t need a church representative since Austen had evolved enough to know that internalised moral behaviour was more important than an explicit “moral” character.

Author

Thanks for your comments. I’m not the expert Brenda is, but I think you would find that she deals with the church very even handedly, neither whitewashing nor vilifying. Jane Austen didn’t preach against the ills of society and the church; she showed examples – good and bad – and let people draw their own conclusions. Reading Brenda’s book revealed some of those subtleties.

No, she did not preach, certainly not with the threadbare morality of a Mary Bennet. She highlighted and oftentimes sketched the obvious.

Thank you, Christina! I hope you will enjoy the book!

Thank you for doing justice to this wonderful resource. I edited Brenda’s book, and when I proofread the advance copy I found myself underlining inspiring passages, nut just correcting typos. Brenda is a meticulous researcher and a clear and careful writer. The result is a highly readable book I’ve already quoted countless times.

Author

Well said, Lori!

Thank you, Lori! You are a wonderful editor and encourager!

To JRTT: You raise many interesting points. My book focuses on “fashionable goodness,” because it was fashionable to appear good, by going to church, but many other aspects of “goodness” did not become fashionable until the next generation, as the book shows. In her novels, Austen criticizes things that were wrong in the church of her time, but also praises what was good, which is why she has both heroes who were clergymen and clergymen who are quite flawed. BTW, Persuasion does have a clergyman, the curate Charles Hayter, and his situation was also a criticism of an issue in the church at the time. The only novel without a clergyman is Sanditon, which of course is only a fragment so we don’t know if Austen would have added one. Even in Sanditon, there is a clergyman who signs the library subscription book, but he is not a character in the few chapters we have.

Yes, i did realise afterwards that Persuasion had a clergyman, and now adding Hayter, there were two, which includes the off-scene Mr Wentworth.

Yes–I feel like someone could write a novel about the off-screen curate, Mr. Wentworth, who gets mentioned but we never see him. He could have his own romance. My chapter on country curates could give the author some ideas. 🙂