While there is no way to know for certain who made up Jane Austen’s circle of acquaintance during her lifetime, it was highly likely that Black Britons were among those with whom she would have been familiar.

While there is no way to know for certain who made up Jane Austen’s circle of acquaintance during her lifetime, it was highly likely that Black Britons were among those with whom she would have been familiar.

The Earliest Black Britons

Evidence of Black Britons exists all the way back to Roman Britain. Archeological analysis of twenty-two sets of remains from Sothwark, Roman London revealed at least one of them had African ancestry. Analysis of the ‘Ivory Bangle Lady’ burial in York suggests a mixed white/Back ancestry. Remains found in 1953 of Beachy Head Lady (dating to 245 AD) in East Sussex, and in 2013 in Fairford, Gloucestershire (dating between 900 and 1000 AD) both appear to be of sub-Saharan African ancestry. Written evidence suggests the presence of residents in Roman Britain from Romanized North Africa, (a section of the coast of modern Algeria, Libya and Tunisia.)

During the Renaissance

As early as the beginning of the fifteen hundreds, Black entertainers could be found in Scotland and the royal courts. “They quickly became not only popular but fashionably essential in England as well.” (Gerzina,1995) Most historians though, suggest the 1555 arrival of five Africans in England to study English and facilitate trade as the start of a continuous Black presence in Britain.

During Queen Elizabeth I’s reign, the Black population of London was mostly made of free individuals many of whom intermarried with native English people. Parish records suggest that many of the Black Londoners were servants, but some worked in local business establishments. (Wood, 2012)

In Early Modern and Georgian England

The Black population in Britain swelled exponentially during the 17th and 18th centuries, fed by the so-called Triangular Trade. Trade ships with goods from Britain exchanged goods for slaves on the coasts of West Africa. Slaves would be transported and sold for labor in plantations. Products of slave labor including sugar and rum would then return to Britain for sale.

The Black population in Britain swelled exponentially during the 17th and 18th centuries, fed by the so-called Triangular Trade. Trade ships with goods from Britain exchanged goods for slaves on the coasts of West Africa. Slaves would be transported and sold for labor in plantations. Products of slave labor including sugar and rum would then return to Britain for sale.

Black communities began to develop and flourish in the port cities most associated with the slave trade, like Liverpool and Bristol. Early Black settlers in these cities included sailors in the merchant navy, soldiers and sailors in Britain’s military, the mixed-race children of traders sent to be educated in England, servants, and freed slaves. (During the American Revolution, slaves fleeing captivity often joined the British armed forces with the promise of freedom in Britain.)

By the mid-18th century, Blacks accounted for somewhere between one and three per cent of the London population. In 1768, some estimated the number of Black servants in London at 20,000, out of a total London population of 676,250. (Others, depending upon the year and the source, put the figure somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000, although the accurate figure is probably closer to 15,000.) (Gerzina 1995) Consequently, by mid-century Black men and women were a relatively familiar sight on the streets of London.

Slavery in Georgian England

Technically, the Cartwright decision of 1569 established that slavery was not legal in England. The 1706 ruling by Lord Chief Justice Holt supported the decision. However, these rulings were routinely ignored and slaves continued to be bought and sold throughout the 1700s.

Finally, the case of James Somersett a fugitive Black slave from Virginia in 1772 legally contested English slavery. Lord Chief Justice William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, ruled that a master could not force a slave to leave the kingdom against his will. Mansfield was clear that his ruling did not abolish slavery per se, and it was vague enough to allow Blacks to continue to be hunted and kidnapped in cities like London, Liverpool and Bristol and sold elsewhere.

Still, the decision helped foster the decline of slavery. The Slave Trade Act of 1807 finally abolished the slave trade, but not the practice of slavery which would wait until the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 to be finally eliminated.

The Black Community of Georgian Britain

Even against this backdrop of slavery, in London especially, a thriving Black community developed, one that evidenced concern for joint action and solidarity. (Gerzina 1995)

Even against this backdrop of slavery, in London especially, a thriving Black community developed, one that evidenced concern for joint action and solidarity. (Gerzina 1995)

“The word ‘Black’ itself was a loose term; those men and women in Britain hailed from many different tribes and regions of Africa. And they spoke several different kinds of English: some, brought up by their aristocrat owners, used refined language; others, educated at sea, used Jack Tar lingo, a stew of Cockney, Creole, Irish, Spanish and low-grade American. All this created great differences in their way of life, and social class played at least as important a role as color in their way of dealing with day-to-day vicissitudes.” (Sandhu, 2011)

These class differences played out in the Black community much as they did in the rest of England. There were those who managed to attain a comfortable, and even prosperous standard of living in the free Black community. Cesar Picton and George Africanus are just two examples of successful Black businessmen. There is evidence of alehouses with a predominantly Black clientele, some owned by Black men, and of the existence of Black social events. It is also clear that Blacks participated fully in the working-class culture of London.

Despite the existence of community, barely 20% of the Black population was female. (Sandhu, 2011) In part because of these gender imbalances and in part because of its social and geographical diffusion, many Black men married local women. (Emsley, et al, version 8.0) In general, mixed-race marriages were not viewed as problematic, mainly because they occurred among the lower working classes. This attitude “is visually clear in the prints and engravings of Hogarth and Rowlandson, among numerous others, as well as in novels and plays, and that race was secondary, to the working class at least.” (Gerzina 1995)

This working class made up the bulk of English society, and an even larger percentage of Black society. But where did the working-class Black people find employment?

For some Black men, a life at sea offered more opportunities than one on land. Although most never advanced far in rank, Black petty officers were not unusual. (Black people in late 18th-century Britain.) These sailors were the exception rather than the rule. For most, domestic service and urban occupations like porters, watermen, basket women, hawkers, and chairmen were the main employments for lower working-class Black Londoners. (Emsley, et al, version 8.0) But even for those who found such employment, the specter of poverty was never far away.

For some Black men, a life at sea offered more opportunities than one on land. Although most never advanced far in rank, Black petty officers were not unusual. (Black people in late 18th-century Britain.) These sailors were the exception rather than the rule. For most, domestic service and urban occupations like porters, watermen, basket women, hawkers, and chairmen were the main employments for lower working-class Black Londoners. (Emsley, et al, version 8.0) But even for those who found such employment, the specter of poverty was never far away.

The Problem of Poverty

In 1731 the Lord Mayor of London ruled that “no Negroes shall be bound apprentices to any Tradesman or Artificer of this City”. Due to this ruling, most were forced into working as servants. (Sandhu, 2011)

During this same period, many former American slave soldiers, who had fought on the side of the British in the American Revolutionary War, were resettled as free men in London. Left without pensions or access to the system of poor relief established by the Old Poor Law, nd often without skills, many of them became poverty-stricken and were reduced to begging on the streets. Thus the “Black poor” became a much-discussed social phenomenon in the final quarter of the eighteenth century. (Gerzina 1995) In truth though, the itinerant of any race had little hope of steady employment and a way out of their situations.

Some poor Blacks found shelter in the areas of St Giles or Seven Dials, St Paul’s, Ratcliff and Limehouse, and along the Wapping riverside. Black people forced to live in such areas shared these unsanitary conditions with poor whites who made up the majority of the population. These were not ghettoes defined by race, but by situation, inhabited by those whose only recourse to starvation and death was often theft, prostitution and beggary. (Gerzina 1995)

Conclusion

Conclusion

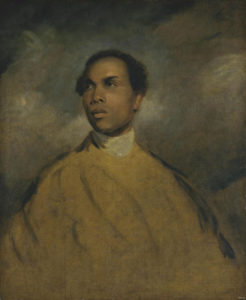

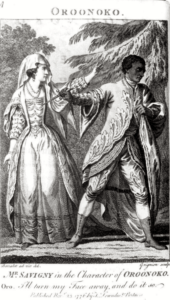

Though the poor were often out of sight and out of mind of the upper classes, this did not mean that Black people were invisible. Even if one lived away from the active Black communities of Georgian England, audiences, both literary and theatrical, were accustomed to seeing Black people in the theatre as both subject and spectators. They also knew them as musicians and performers at fairs. Black Britons were an active part of British society during Jane Austen’s day.

This post only scratches the surface, just highlighting a few points in a broad and important topic. Some of the references below might be helpful in gaining deeper understandings.

References

“Black Lives in England.” Historic England. 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020. https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/the-slave-trade-and-abolition/sites-of-memory/Black-lives-in-england/

“Black people in late 18th-century Britain.” English Heritage. Accessed July 12, 2020. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/portchester-castle/history-and-stories/Black-people-in-late-18th-century-britain/

Alliance for Workers’ Liberty. “A Short History of Black people in Britain.” Worker’s Liberty. March, 23, 2006. Accessed July 9, 2020. https://www.workersliberty.org/story/2017-07-26/short-history-Black-people-britain

Edwards, Paul. “The History of Black People in Britain.” History Today. September 9, 1981. Accessed 7/1/2020. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/history-Black-people-britain

Emsley, Clive; Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker, “Community Histories; Black Communities”, Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, July 12, 2020). https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/Black.jsp

Gerzina, Gretchen, Black London: Life Before Emancipation, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1995.

Glover, Dominic. “The First Black Briton? 1000 Year Old Skeleton of African Woman Discovered by Schoolboys in Gloucestershire River.” International Business Times. October 2, 2013. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/fairford-sub-sahara-africa-skeleton-gloucestershire-507102

Martin, S.I.. “African writers and Black thought in 18th-century Britain.” Discovering Literature: Restoration & 18th Century. June 21, 2018. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.bl.uk/restoration-18th-century-literature/articles/african-writers-and-Black-thought-in-18th-century-britain

Rebecca C Redfern, Michael Marshall, Katherine Eaton, Hendrik Poinar. “‘Written in Bone’: New discoveries about the Lives and Burials of Four Roman Londoners”. Britannia 48 (2017), 253-277, doi:10.1017/S0068113X17000216. Accessed July 12, 2020. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/britannia/article/written-in-bone-new-discoveries-about-the-lives-and-burials-of-four-roman-londoners/F464D9E93FCE96341DDD7774C4C8CA10/core-reader

Sandhu, Sukhdev. “The First Black Britons.” BBC History. February, 17, 2011. Accessed 7/3/2020.

Seaman, Jo. “The mystery of Beachy Head Lady: A Roman African from Eastbourne.” Museum Crush. May 4, 2018. Accessed July 12, 2020. https://museumcrush.org/the-mystery-of-beachy-head-lady-a-roman-african-from-eastbourne/

Wood, Michael. “Britain’s first Black community in Elizabethan London” BBC News. 20 July 2012. Accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-18903391

29 comments

1 pings

Skip to comment form

Thanks so much for this post and especially for research and sources you provided! I’m always impressed with your writing, both fiction and nonfiction. All the best, Christina

Not allowing people of African origin to become apprentices was a huge problem, because the Guilds maintained a tight control of all skilled workers in London. If you tried to set up work without officially serving as an apprentice for seven years, you could be imprisoned. This link explains the implications in more detail. https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Apprenticeship_in_England.

Thank you for providing this overview, Grace.

Very good research, might I also suggest David Olusoga’s Black and British. As for Jane Austen, one would hardly expect to find much racial diversity in her writings since she barely provides class diversity. And this has long been a complaint about her writings. My first real encounter with a person of colour in classic English literature was in Dickens’ Dombey and Son and that still was very sparing. But I feel certain there were more than just allusions in other classics, Defoe’s Man Friday comes to mind and I think there may have been something in cleland’s Fanny hill. Regardless, Austen apparently steered clear of blandly introducing highly contentious issues (both in her day as well as ours and perhaps even more in hers!) into her, what are essentially love stories. That does not mean however, that she steered clear altogether; Sir Thomas had clear links to slavery and it has been speculated that wealthy men “from the north of England” also did as well. These small hints provide a wealth of opportunity for JAFF to delve into and explore since one of JAFF’s strengths has been to add to her stories what are have not been written but known to exist. This however, also presents a disadvantage to the JAFF community since many of the established and not so established writers are not persons of colour and representation of people of colour not only requires that they be but demand it. So it opens up a whole new area of discussion that the JAFF community largely balks at because conversations can get sensitive and highly acrimonious (I should know, I have been involved in a few myself and have probably judged people unfairly during those). I do believe however that JAFF can only become richer for increasing its space for inclusion and diversity and the writings deeper and more meaningful. Jane Austen focuses on human themes that are universal and makes her books universally appealing and appreciated but societies have evolved and continue to evolve to make universality more individual where people find that they need to see themselves as not ‘the other’ and where diversity of humans are presented as so very commonplace and accepted that it is a non-issue.

I was about to suggest Olusoga’s book myself. Agree that this is an excellent and informative summary that points the way towards further research rabbit holes for me.

Got it on Kindle, but I haven’t read it yet. Thank you both for the suggestion.

This is an impressive, thorough, much needed summary. of people of African descent in England. I am grateful for the hard work that went into it, and the factual presentation which provides essential information without acrimonious attacks on and judgement of people who are slowly coming to learn more about the diversity of people in England. The challenge to the JAFF community is to find ways to weave this awareness into stories, painting the scenes with greater depth of awareness, weaving in the reality of diversity and the wrongs caused by cultural ignorance and arrogance while still keeping the focus on telling the tales of overcoming obstacles to happily ever afters. Many authors have dealt with various social ills of the period, including the mills, mining and trafficking of young women, the blind arrogance of the institutional church and some of its clergy – as well as some clergy who actually tried to do their best to follow their calling. Maria Grace’s dragon books address prejudice and racial disparity through creative world-building and provide much to reflect upon about our own unthinking biases. We all have a long way to go. We all need to learn more about putting ourselves in others’ shoes, insofar as that is possible. This helpful information gives us more ways to do just that.

Diana, you put it so perfectly. Thank you.

Thank -you for such illuminating research into Blacks in England. My heritage consists of Irish, English, French, and

African. Interestingly, my love of British Literature began long before I had conclusive proof of my ancestry. Regency is my favorite era, but from Beowulf onward captured my studies during my undergraduate years many Shakespeare classes ago. So, thank-you!! Love JA, too.

Thanks for a great and much needed summary, Maria Grace! Another reference I’ve found useful for Black history is Peter Fryer’s Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain.

This was a super-interesting post, thank you! And thanks also for the great list of references. 🙂

Outstanding post, Maria Grace! And some excellent, well-thought-out comments here, also. As you said, this is just a brief summary of an important topic, but I’m excited to do a deeper dive into some of the references you cited. Honestly, your posts on Regency England are always fascinating and have taught me so much. 🙂

Thanks for sharing!

Fascinating and enlightening post. I’m eager to look into some of these historical resources. Thanks!

Thank you so much for sharing this extremely information. This is research is wonderful and something I have often wondered about. I have done a lot of research on slaves and free blacks in the United States during the same time as a historian. Jane Austen does make references to slavery in Mansfield Park and Sanditon, which naturally leads to an appertite of readers for more. After all Queen Victoria would later dislike slavery, and early on it would be abolished in the British Empire. Really interesting questions are raised in Mansfield Park. Anyway this is appreciated very much.

Thank you for your research and posting. A posting on another website with a similar theme was deleted – apparently as not wanting to be divisive. I thank the authors here for giving us a forum where we can learn, discuss, and question.

What a well researched and informative part of history.

Nathaniel Wells of Piercefield House in Monmouthshire is a rare, perhaps unique, example of a black man owning a large country estate in Regency Britain.

Wells was the mixed-race son of a plantation owner and an enslaved woman. Educated in England, after inheriting his father’s vast fortune he bought an estate, held a commission as Lieutenant in the local yeomanry, married a society beauty, became a magistrate, High Sheriff and eventually the Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Monmouthshire. In his old age he retired to live in Bath.

It was a far cry from the usual life of a black person in 19th century Britain but, as Austen acknowledged with her character Miss Lambe, wealth could bear down even Regency social barriers.

Although it covers an earlier period than Austen’s anyone interested in Black British history might enjoy Dr. Miranda Kauffman’s book ‘Black Tudors’ (2018). It’s well-researched and very readable.

I read about this on Twitter where she actually had to defend her book against people who refused to believe there were black persons in Britain during the Tudor period. Persons, one assumes, who were heavily influenced by The Tudors tv series lol.

I believe so, though I haven’t followed this closely; but I have read her book and it’s very interesting. It focuses on the lives of ten individuals, but there are a lot of references to others she found in her archival research. I was pretty amazed to learn that the diver who salvaged cannon from Henry VIII’s flagship ‘Mary Rose’ not long after she sank was from West Africa. He worked for a Venetian salvage operator and was used to free-diving in the Mediterranean. Pretty different diving into the cold dark waters off Portsmouth I should think. And to be honest it’s a job I wouldn’t want myself, not with all those bloated, drowned corpses swishing about…

Looks like a very useful reference, Rita. Will have to check it out.

I’ve been thinking about what you said about the attacks on ‘Black Tudors’. In Britain (and other European countries too no doubt) it’s been easy in the past for the existence of historical black individuals to be overlooked, or outright forgotten, because their numbers were relatively few and gender imbalance meant they often married locals and so didn’t survive as a distinct community. Their children just vanished into the general population.

It’s surprising in how few generations people can lose all knowledge of their ancestry. A while ago I happened on this site by Stella Halliwell (http://stellahalliwell.co.uk/pre-raphaelites/fanny-eaton-the-forgotten-pre-raphaelite-stunner/) On it there’s a lovely portrait of the Pre-Raphaelite model Fanny Eaton, who came from Jamaica to London in the 1840s. Mrs Eaton only died in 1924 – that’s not even a century ago – and yet as you can read in the comments below her portrait on this site, at least two of her descendants were absolutely unaware of their heritage.

I believe this has happened multiple times in the past, which is why people like the ones who attacked Dr Kaufmann’s book genuinely struggle to get on terms with the fact that there have been some black people in Britain for pretty much most of its history. Not as big a percentage of the population as today by any means but yes, always historically present.

Correction to my post about ‘Black Tudors’ – the author’s name is Dr. Miranda Kaufmann. Apologies to anyone who googled it under the wrong spelling 🙁

As always, your research and presentation of factual information is thorough and detailed in the historical context of the era. I have bookmarked this link for future reference and research. I sincerely appreciate the professional and politically neutral tone of this post.

Oh btw, I would also like to suggest the Samuel Selvon novel – The Lonely Londoners. It’s been awhile since I’ve read it but I remember it moving me in high school. It’s set amidst the ‘Windrush Generation’ of the 1950s and can give insights into the thoughts, ideas and language styles of Caribbean migrants which can probably be extrapolated back 130 years…perhaps lol. Anyway, it’s a good read.

Thank you for the cogent summary and references. I’ll be back to read this a few times.

I know this is vague but I wondered if anyone on here knows anything about Richard Tyson(1735-1820), sometime the Master of Ceremonies at the New Rooms in Bath? I can’t find much about him but there’s a snide reference I once came across in ‘The Times’ newspaper archive in which he’s referred to as a ‘Creole’. I’m not sure what that means at this date.

The background was, Tyson had banned somebody from the Rooms and they weren’t happy about it. The Times prints an extract from a letter of protest:

“…but the new elected master of the ceremonies of the upper rooms (though a Creole and not very fair) objected to the person of Mr. M. and refused to let him dance…”(The Times, 15 December 1785, p.3)

I’m not clear whether ‘Creole’ here just meant a white person born in the colonies. But it sounds like the complainant is trying to get a dig at Tyson by implying he may be mixed race (“though a Creole and not very fair”). Tyson’s portraits online don’t suggest this. His will though makes a reference to the Conarees plantation on St Christopher owned by a Thomas Tyson, so he clearly had a connection to the West Indies.

But I’d argue that whether the aggrieved ‘Mr. M ‘ who got banned from the upper rooms was really claiming Tyson was mixed race, or whether he was just alluding to it as a possibility doesn’t matter in a way. It still shows wealthy West Indians were seen as part of the fashionable world, even if some whites might resent it.

But of course Tyson may have ceased to be MC before Austen came to Bath, so she may never have seen him.

While it’s very tempting to consider Tyson to have been a mulatto it might be more probable for him to have been a white who had been born and grew up in the tropics and therefore had a naturally tanned and darker complexion. Either way, it makes for an intriguing back story.

Thank you for posting this!

[…] Esse texto é uma tradução do artigo da autora Maria Grace publicado aqui. […]