Whenever we think about writing in the ‘old days’ our minds go directly to the image of a quill pen. Quill pens date back to the Middle Ages, as far back as the 6th century. They were a vast improvement over their predecessor, the reed or cane pen, used for writing on papyrus, whose origins can be traced back to 800 BC. Reeds are brittle, do not retain a sharp point, and require about eight inches of usable material for writing. Since quills are more durable, hold a point longer and are useful until very little remains, they were a vast improvement over reeds, and are still in use today by some calligraphers.

Few of us use them today though, so the question: how did one use a quill pen and what was it like to write with one?

Beginning at the beginning

Jonathunder, GFDL 1.2 http://www.gnu.org/licenses/old-licenses/fdl-1.2.html, via Wikimedia Commons

Turning a feather into a pen was not as simple as finding a convenient bird, plucking a feather and dipping it in ink. The complex process began with acquiring the right feather.

Not just any feather was suitable for a quill pen. The best pens quills were those from primary flight feathers taken from large, living birds. (Feathers from living birds were much stronger.) Goose, turkey and swan feathers were highly prized for use as writing quills.

Goose feathers made the most popular pens for writing. Swan pens produced very broad lines. In contrast, crow feathers produced very fine, flexible pen nibs, favored by artists and ladies who wrote with small, delicate lines.

A healthy goose could produce about twenty pen-quills a year. Large flocks of geese were maintained for the sole purpose of producing pen-quills. But England could not keep up with its own demand for feathers, so a brisk feather trade developed. By 1835, twenty million quill feathers were imported from Europe, primarily Netherlands, Norway, Iceland, Germany, Russia and Poland.

Feather from the left wing were favored because the curve made them easier for right-handed writers to use. Left-handers preferred pens made from the right wing. Once gathered, the feathers were sorted into three grades: primes, seconds, and pinions, depending on the length and thickness of the quill.

Dressing the Quill

Once plucked, the feathers required tempering, which would strengthen and de-grease the feather’s barrel. Without this process, the quill cannot be cut into a clean slit that would allow ink to flow smoothly, essential to a proper pen nib.

Tempering or quill-dutching involved heating the quill shaft to harden it. This could be accomplished with hot ashes, hot water or hot sand. During this process, the quill might be flattened or shaped somewhat, and the outer and inner membranes would be removed. A more uniform appearance could be achieved with an aqua fortis (nitric acid) treatment, but some felt that resulted in brittle quills. So, many quills sold to clerks, who needed especially durable pens, were not treated.

Finally, the feathery part of the quill, the barbs, would be stripped away, in all or in part, making the quill far less showing but far more convenient to use and ship. Quills were then bundled up and send to stationers’ shops. They might be sold to consumers in this state, but more often pen cutters would prepare them for final sale.

Cutting a Quill

Cutting quills required particular skills, time and patience, which could be learned. Many books included instructions for the task. However, Dr. Parkins, Young Men’s Companion (1811) suggests:

THIS is gained sooner by Experience, and Observation from others who can make a Pen well, than by verbal Directions. ….

~Parkins, 1811

You can watch how it was done here:

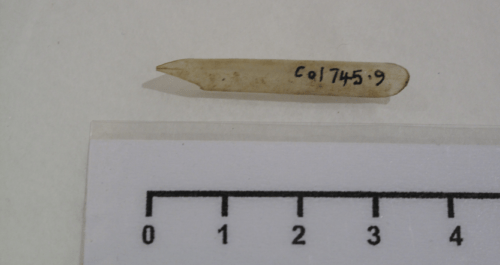

Pens might be sold in the form of the entire quill, but often quill nibs were sold alone. Nibs like this had been available for more than a century by the time Jane Austen was born. The nibs would be fit into a holder, which could be as simple or extravagant as the user desired. In 1810-1815 a box of twenty-five quill nibs cost three shillings. By 1822, one hundred could be bought for that same price.

Using a quill pen

Writing with a quill pen is a very different experience from writing with a modern fountain pen or ballpoint pen. Quill nibs are very delicate and cannot take the pressure of a heavy hand. So, writing would usually have been done over a felt cushion to preserve the pen’s tip as long as possible.

Several quills would have usually be used in writing a single document, not because the pens would wear out, but because, during the course of writing, the pen softens as ink is absorbed into the nib. When a pen became too soft, it would be wiped down and set aside to dry, while a new pen was pressed into service. As many as three or four quills might be required to write a letter.

Correct posture and hand position were required to keep the pen from wearing unevenly. Fast writing or too much hand pressure caused ink blots and sprays. Such bad habits would result in pens that needed to be mended or re-cut often. Most people mended their own pens, trimming away the dull and misshapen bits, to return them to their original shape.

Depending on one’s writing habits, a person could get a week’s worth of writing from a quill before there was not enough left of it to re-cut. Makes one wonder, how many quills Jane Austen would have used in a week, doesn’t it?

References

History of Quill Pens. History of Pencils. Accessed 11/21/22. http://www.historyofpencils.com/writing-instruments-history/history-of-quill-pens/

How to Ruin a Feather to Make a Pen. Her Reputation for Accomplishment. June, 21, 2014. Accessed 11/14/2022. https://herreputationforaccomplishment.wordpress.com/2014/06/21/how-to-ruin-a-feather-and-make-a-pen/

HURFORD, ROBERT. Handwriting in the Time of Jane Austen. PERSUASIONS ON-LINE V.30, NO.1 (Winter 2009). Accessed 11/28/22. https://jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol30no1/hurford.html

Kane, Kathryn. The Quill, the Regency Pen. Regency Redingote. September, 11, 2009. Accessed 11/01/22. https://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2009/09/11/the-quill-the-regency-pen/

Manufacturing Quill Pens. Her Reputation for Accomplishment. June 19, 2014. Accessed 11/14/2022. https://herreputationforaccomplishment.wordpress.com/2014/06/19/manufacturing-quill-pens/

Parkins, Dr. Young Man’s Best Companion. Thomas Tego: London. 1811

Shaw, Ariel. Facts and History of Quill Pens. Pen’s Guide. April 5, 2019. Accessed 11/21/22. https://pensguide.com/facts-and-history-of-the-quill-pen/

The Pen in Penmanship. Her Reputation for Accomplishment. June 16, 2012. Accessed 11/14/2022. https://herreputationforaccomplishment.wordpress.com/2014/06/16/the-pen-in-penmanship/

5 comments

Skip to comment form

I’ve never tried writing with a quill but as a child at school my first pen was a wooden dip pen with a replaceable nib and we had an ink well in the top of the desk. When I started at the Grammar School I used biros until my eldest brother started work and bought me a Parker fountain pen and propelling pencil set for my birthday! I loved it and still have it 58 years later. I’ve always been fascinated by calligraphy and illuminated letters.

Gotta wonder how the geese felt about having their feathers removed, while they were still using them! And, was removing a feather difficult?

I always appreciate your thoroughly researched articles on history, Maria Grace! It’s amazing to think of how different the writing experience must have been for Austen. I wonder what she would think about modern pens…and computers? (Makes me think of how much Amy D’Orzio’s version of Darcy in her short story “The Travelers” loved modern Elizabeth’s bic pen!) Thanks again for this fascinating article!

That is very interesting.

I’m so glad to learn that the birds were still alive after their feather were pluck…

(or maybe not so glad now actually thinking about it… @@)

Thank you for sharing your research!!

Your research was quite thorough and I definitely learned a number of things about quill pens I never knew before….. e.g., several pens would be used in the course of writing a letter because the quill would get soft from the ink; whatever that was written was often done by putting the paper on a soft cushion to insure the writer did not use a heavy hand; right and left handed people used quill feathers from the left and right wings of the bird respectively; although pens could be trimmed as they wore out, due to its size a pen might not last a week after all the trimming….etc, etc. We all know that Caroline was only too willing to trim Darcy’s pen and Bingley obviously wrote with a heavy hand because of all the ink blobs he left behind… but there is so much more to know about quill pens of which you have now enlightened us. Thank you!