If you are ill, injured, or pregnant and live in England during the Regency Era, who do you call for help and what would they do to diagnose and treat you?

Made of wood and brass, this is one of the original stethoscopes belonging to the French physician Rene Theophile Laennec (1781-1826). It consists of a single hollow tube.

Except in obstetrics, medical care did not change in any fundamental way during the 150 years between 1700 and 1850. There were inventions, such as the stethoscope invented by the French physician Laennec in 1819, but until the acceptance of the concept of infectious disease caused by micro-organisms (AKA The Germ Theory) in the second half of the 19th Century, the theory of medical treatments remained essentially unchanged. This stagnation was worsened in the late Georgian and Regency Eras by the Napoleonic Wars, which significantly decreased travel in continental Europe by English physicians and so limited the transmission of medical knowledge from Paris and Vienna, major centers of medical advancement of the time.

Physicians

Physicians were trained in England at medical schools; the only requirement for admission was the ability to pay the tuition and learning was limited to attending lectures. There were few or no practical or hands-on teaching sessions as physicians did not perform any procedures or surgeries. In some cities in Scotland, and on the Continent, a medical diploma could be obtained by mail order. This separation of medical and surgical treatment was the result of societal mores which prevented “gentlemen” from working with their hands, a situation that began in the middle ages (when the only surgeons were barbers, who had the sharp knives).

Physicians treated their patients with medicines which they or an apothecary would compound. A physical exam would consist of looking at the patient’s skin color, temperature, and turgor, along with taking his or her pulse. They were unable to listen to the heart to try to determine if it was functioning normally as Laennec’s stethoscope (a hard tube for the physician to listen to the chest) was not invented until 1819 and was not widely known and accepted by English practitioners until well into the 19th Century.

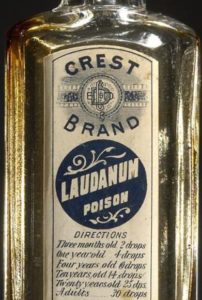

Laudanum bottle

The primary medication used by physicians was some form of opium (usually tincture of opium, often mixed with other ingredients). In addition to it’s excellent pain relieving qualities, it was also used for some of its side effects, such as drowsiness and constipation, to treat hysteria, insomnia, and diarrhea. Laudanum was a tincture of opium and was freely prescribed, but could also be purchased over the counter from the apothecary directly. Not surprisingly, there were many people addicted to Laudanum in the 19th Century. Laudanum and Paregoric (another concoction with an opium derivative which was generally used for GI disorders and cough) continued to be readily available (but by prescription only!) until the middle of the 20th Century.

Practitioners also used blood-letting to treat many diseases under the theory that if you are hot and red you should be bled to make you cool and pale. Physicians did not usually do this themselves (can’t work with your hands if you want to be a gentleman!) but would have an apothecary or surgeon do it. It is very disconcerting to modern sensibilities to think of treating an infection after a gunshot wound with blood-letting!

Surgeons

Surgeons in the Georgian Era had long been separated from barbers, but they continued to be a completely separate branch of medical care from physicians. Surgeons were not required to go to medical school, but were trained by apprenticeship like any other trade, as they were considered tradesmen. For this reason, professional surgeons have always been called “Mr.” in England, unlike physicians, who are called “Dr.” This has translated in modern practice to an English surgeon attending medical school and being called “Dr.” until he finishes his surgical training, at which time he goes back to “Mr.” As the 18th Century progressed, more and more surgeons attended lectures in medical schools and gradually became more professional about their field, but until the development of anesthesia (ether) and sterile technique in the second half of the 19th Century they were limited in what they could do.

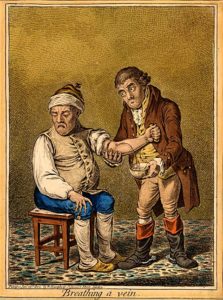

“Breathing” a vein (bloodletting)

Most of the practice of surgeons was in setting bones, removing bullets, stitching up wounds, and bleeding patients. An important part of the practice in the first half of the 18th Century was in obstetrics; when a midwife gave up on a difficult case and either the mother or child (or both) was going to die the surgeon was called in to try and save one of them. Not surprisingly, the association in the minds of the public between surgeons and obstetrics cases was that of death, not of a practitioner coming in to try and save someone’s life.

Apothecaries

Apothecaries, or pharmacists as they are now known, were not legal practitioners of medicine, but they were the people who had the drugs and common usage in the 18th and 19th Centuries was for people who did not have a physician, or who could not afford a physician, to ask the apothecary for advice. As time went on he was called to peoples’ houses to prescribe for those who were ill, and many upper class households used an apothecary for the servants and a physician for the family. The apothecary could not legally charge for his advice, but only for the drugs which he prescribed.

Traditional apothecary shop

It was not until 1815 that a law was passed requiring licensing of apothecaries, but the law was universally despised by medical practitioners who had been competing with apothecaries for patients for centuries and the law was rarely enforced anyway because of the great confusion of responsibility for the enforcement of the law.

Attempts by physicians to discredit apothecaries and bring the force of the law down on them for practicing medicine without a license at the beginning of the 18th Century failed because apothecaries had been seeing patients for so long that the law viewed it as acceptable, even though it was not condoned by the legal codes. If it was okay for apothecaries to openly treat patients in the 17th and 18th centuries without anyone questioning it, then it became common law and the apothecaries were protected as long as they did not injure someone with their treatments.

Midwives

Midwives, until the second half of the 18th Century, were almost always women who gained some experience delivering babies and who gained their job by default of other practitioners as having men involved in the intimate process of delivery was abhorrent to most women of the time- it was unthinkable! Then male surgeons, who were already considered tradesmen, began infringing on this all-female monopoly and brought medical science (such as it was) into the practice of what is now known as obstetrics. This change was largely brought about by the demands of the gentry and peers for healthy heirs to their estates. This was so important in the smooth inheritance of vast amounts of English land that the man-midwives, also called accoucheurs, were actually accepted into the upper echelons of society in a way that no other surgeons had been. No accoucheur would have been invited to dinner by the haute ton, but one, William Knightley, was knighted for his service to the crown (he was the Prince Regent’s personal practitioner at the time) and was actually given a post as advisor to the Regent in government matters. Clearly, he was seen by the Regent as a man of acumen and wisdom.

Herbalists

People who lived in rural areas or who could not afford the care of a physician or the cost of medications from the apothecary could seek out their local herbalist. Herbalists were usually women who had gained knowledge passed down from previous generations on the properties of herbs and other plants and how they could be combined to treat different ailments. Many women who ran large households also learned to use herbs to treat the various ailments of the servants and family members. The supervised herb gardens and then the drying of herbs for use in the winter, as well as in the compounding the medications in the stillroom.

People who lived in rural areas or who could not afford the care of a physician or the cost of medications from the apothecary could seek out their local herbalist. Herbalists were usually women who had gained knowledge passed down from previous generations on the properties of herbs and other plants and how they could be combined to treat different ailments. Many women who ran large households also learned to use herbs to treat the various ailments of the servants and family members. The supervised herb gardens and then the drying of herbs for use in the winter, as well as in the compounding the medications in the stillroom.

Herbalists had been around since the Dark Ages, but during these early times it could be risky to have too much knowledge about these mysterious subjects because if the patient did not do well under your care you could be accused of being a witch, casting evil spells on your neighbors. If you have never tried, I can assure you that it is virtually impossible to prove that you are NOT a witch!! My eldest son had a Western Civilization teacher in high school who gave the students an assignment for the next class: prove in a court of law that you are not a witch. The teacher was the judge and you had to be able to answer his questions and overcome his arguments to be prove innocent. The students loved it and they learned A LOT about the Dark Ages in the process!

7 comments

Skip to comment form

Thanks for this overview – very useful! I’m guessing then that in Pride & Prejudice an apothecary treated Jane because the area was too rural to have easy access to a physician?

Author

That’s what I have always assumed. An apothecary would have been less expensive as well- Mrs. Bennet might have thought her daughters could make do so she could buy a new gown this season! 🙂

Very interesting and informative! Thanks for sharing.

Great topic. Our JASNA group had talked of having a discussion regarding medicine in Jane Austen’s time period. Would you be willing to share your sources??

Author

I’d be happy to, but I’m not sure I can come up with many of them. My understanding of Regency medicine began in medical school (medical history was one of our classes) and I’ve picked up bits and pieces all over the place- from Wikipedia to the OED! If you have any specific questions I could try to help. I also have a PowerPoint from a course I gave at the RWA a few years ago and I have given an online course for them, too. I have a lot of books on various aspects of history of medicine which I can share if you would like the names.

Fascinating post! Thanks for sharing.

So very glad I live in the present.