Today, paper is quite literally something that grows on trees. It is abundant, disposable, and cheap, quite the opposite of the situation during Jane Austen’s day when paper was something of a luxury good

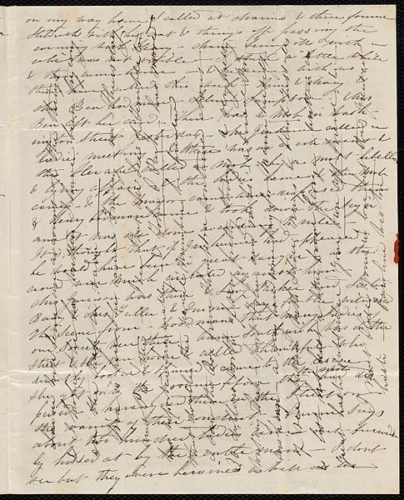

This, and the cost of postage, explains why letters of Austen’s era were cross-written, sometimes three different times. A writer would write a page full, turn the page 90 degrees and write again, and then if quite long-winded, turn it 45 degrees and fill it again, getting three times the writing into a single sheet letter. Of course, that made it hard to read, but the price of paper and postage made the sacrifice worthwhile.

Parchment and Vellum are not Paper

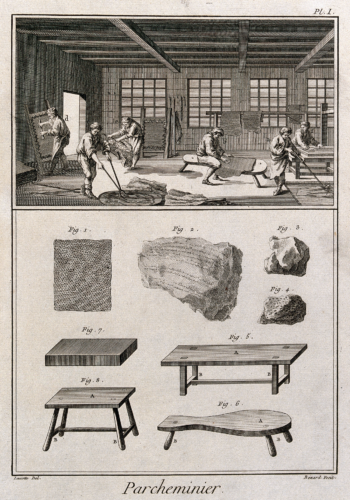

Parchment makers’ workshop: interior view (a) stretching out the skins (b) elevations of various tables and skins used. Etching by Bénard after Lucotte .http://catalogue.wellcomelibrary.org/record=b1195618 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Prior to the paper as we know it today, parchment or vellum were used for writing. Both were animal-based writing media whereas paper has always been vegetable based.

Parchment is made from untanned sheep or goat skin, whereas vellum comes from untanned calfskin. To prepare them for writing, the skins are soaked, first in water to clean them, then in a lime solution to remove the hair. While still wet, the skins are stretched on frames and scraped with a special knife to remove remaining hair and create a uniform thickness. Powdered pumice may then be used to smooth the surface for a pen nib and make the ink it carried more readily absorbed. Other calcium containing treatments might be used to further degrease and bleach the skin. Finally, the skins are be dried, then cut down to the necessary size.

Because of the animal-based, labor-intensive process, parchment and vellum are (and were) far too expensive to be used for mundane writing purposes. What were parchment and vellum used for? Books of the medieval period were written or printed on parchment. Legal documents, government documents and university diplomas were also inscribed on parchment/vellum.

Making Paper

In contrast to parchment and vellum, paper has always been made from plant materials. Papyrus, the first plant-based writing materials date to the 4th century BC Egypt and the use of amate bark dates to the pre-Columbian period in the Americas. True paper making began during the Eastern Han Period in China. (25-220 AD) using a combination of milled plant fibers (mulberry and bast) and textile fibers (old rags, nets and hemp waste). During the 8th, Chinese papermaking replaced papyrus in the Islamic world. By the 11th century, it reached Europe. Two centuries later, in Spain, the process became mechanized with paper mills that used waterwheels.

In Europe, paper was made primarily from linen rags. Ragmen would travel through town and country collecting rags to sell to the paper mills. During the late 17th century linen rags were in such short supply that some parts of Europe forbid trade in rags outside national boundaries (which led to smuggling but that is another subject) and the English Parliament passed a law in 1666 forbidding the use of linen burial shrouds, requiring wool instead. This served the dual purpose of conserving linen for paper and bolstering the English wool industry. These laws remain in place until the Regency era when both linen and cotton rags became more available, and papermaking processes improved to allow cotton fibers alone to be used in papermaking. Still though, paper production remained limited, until the mid-19th century.

Spinning Rags into Paper

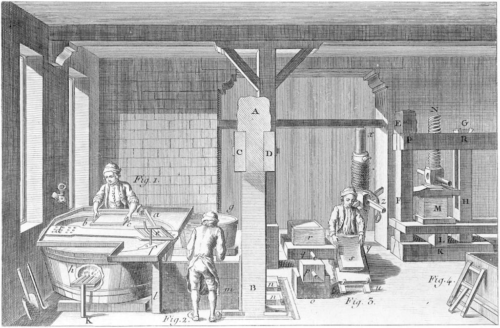

The process of turning rags into paper began with sorting and cleaning the fibers. Afterwards, the fibers would be soaked in water and beaten with heavy wood and metal stampers that broke down the fibers. Water wheels powered the earliest stampers, but eventually steam powered stampers took over. The mechanized hollander, a drum with a roller set with knives that spun through the wet rags made the pulping process more efficient. Like the stampers which preceded them, hollanders were often usually water or steam driven.

Once the rags had been turned into pulp, wooden molds—frames containing a wire mesh—were dipped into the pulp. The water flowed away, leaving a thin layer of fiber behind. The papermaker would then level the fibers and shake out the excess water, creating a nascent paper sheet. These sheets would be turned out and layered with felt pads into stacks which were then put through a press to squeeze out excess water. Pressed sheets were then hung to dry.

Early paper molds had wires running only one direction and produced a paper with a distinct grain called ‘laid’. Laid molds did not work very well with the short fibers in cotton pulp and produced a paper that did not cut easily or evenly when folded into quartos used in book manufacturing. Improved ‘wove’ molds were developed which featured wires running both vertically and horizontally, like a mesh screen. These molds allowed paper to be produced with only cotton fibers and created sheets without a distinct grain, making them better suited for book printing.

At the beginning of the 19th century, papermaking took another leap forward when Nicholas Louis Robert patented a machine that automated the papermaking process. It produced a continuous length of paper that was then cut into sheets. An explosion of papermills in Europe and America followed, increasing availability and reducing the price of paper.

There Has to Be a Better Way

No good turn goes unpunished, though, between the improvements in paper production, better printing presses, and a rising demand for books, demand for paper soared. The supply of rags could not keep up with demand and an intense search for alternative plant fibers to turn into paper began. Asbestos, straw, swamp grass, dune grass, marsh mallow and even deinked waste paper were all examined as possible alternatives.

Wood pulp, which would become the new standard for papermaking was first explored by Matthias Kops in 1800, but did not become economically viable until the middle of the century.

Foolscap

At the beginning of the 1800’s, people bought their paper from stationers. Stationers would receive the paper in bales of 10 reams each containing four hundred and eighty sheets. A customer might then purchase as little as a single sheet might, but quires of twenty-four sheets were the most common purchase.

This paper was often referred to as foolscap for the original watermark used to denote the standardized size of the paper, 16 ½” x 13 ¼”. A slightly smaller size, called a pott as 15 ½”x12 ¼”. It was the smallest size generally available. Larger sheets were available, up to a size known as a double elephant at 39½ ”x 26½”.

Because paper was expensive, these large sheets were often cut down with a pen knife, or better a paperknife, into exactly the size needed.

Today, once we have pen and paper in hand, we are generally ready to get to the task of writing. Not so in the Regency era, though. Quill and paper were just the beginning. A bit more equipment and several more supplies would yet be necessary for the task. Next time we’ll explore paper knives, rulers, and pounce.

I’ve been taking paper for granted for nearly my entire life. What about you? Tell me in the comments.

Find more on the art of writing here.

Find out more about the British Post here.

Find out more about letter writing here.

References

Hurford, Robert. Handwriting in the Time of Jane Austen. PERSUASIONS ON-LINE V.30, NO.1 (Winter 2009). Accessed 11/28/22. https://jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol30no1/hurford.html

Kane, Katheryn. Oh, Foolish Foolscap. The Regency Redingote. October, 31, 2008. Accessed December 12, 2022. https://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2008/10/31/oh-foolish-foolscap/

Kane, Katheryn. Parchment is not Paper. The Regency Redingote. August, 21, 2009. Accessed December 12, 2022 https://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/2009/08/21/parchment-is-not-paper/

Richmond, Arietta. Paper in the Early 1800s. Arietta Richmond. January 27, 2018. Accessed Feb, 14, 2023.https://ariettarichmond.com/paper-early-1800s/

Valente , AJ. “Changes in Print Paper During the 19th Century” (2010). Proceedings of the Charleston Library Conference. http://dx.doi.org/10.5703/1288284314836

4 comments

Skip to comment form

Thank you for this very interesting post!

Wow, what a thorough explanation of the paper-making and the history of paper! Thank you, Maria Grace! I definitely take paper for granted, but I’ll think more about it now. I do remember writing about Elinor Dashwood trying to conserve her drawing paper because of expenses. So much of the artistic process (for writing, as well as drawing) must have been different when the creators had to consider the finite resources they had at their disposal. I can’t think of how many words I type, then delete, then type again because there’s no consequence. I think I would have had to spend more time composing sentences in my head before writing if I had to concern myself with my supply of paper (not to mention ink, quills, and just the time and exertion of writing by hand). Thanks again, Maria Grace!

Thanks for this informative and interesting post! Imagine having to be so much more thoughtful and deliberative when using such a precious and expensive resource.

Great article. Could you tell me please what paper that can be purchased today is the nearest to that used by Jane Austen and her contemporaries?