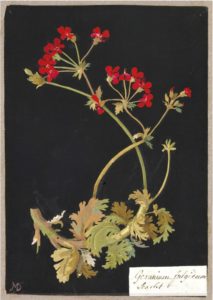

Geraniums by Mary Delany (1700-1788)

It had been an exceptionally wet October with winds and gales blowing around Mansfield Park almost daily, and Fanny was thankful to have recourse to her own dear East Room. This had been the Bertram sisters’ former school-room, now Fanny’s own refuge; but it was a chilly refuge in the inclement weather, for Fanny was not allowed a fire, by decree of her Aunt Norris, who lost no opportunity to treat her meanly in emphasis of her lowly status. It took some considerable amount of afternoon sunshine, in fall and winter, to warm the room; and that was in short supply.

To be sure, there was warmth and light aplenty down-stairs, but Fanny had reason to seek the East Room for peace and comfort in order to avoid the down-stairs doings almost as much as the bad weather. For the house was all alive with acting. Fanny did not object to acting itself; on the contrary, to her, who had never in her life witnessed a play, watching scenes being read and improved upon was a very great interest and entertainment, and although she could not, would not act herself, she had been glad to make herself useful in every way she could, from helping Mr. Rushworth remember at least some of his lines, to sewing on Mrs. Norris’s interminable green baize curtains.

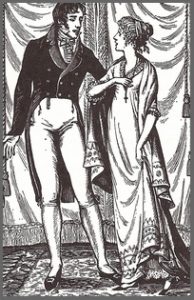

Mansfield Park illustration by Joan Hassall

There were some aspects of the acting scheme, however, that were inexpressibly painful to her. First and foremost was being forced to witness the spectacle of her dearest cousin Edmund acting with the too charming, too attractive Mary Crawford, visibly demonstrating how he was losing his heart to her. As they played the lovers in “Lovers Vows”, it was terrible to Fanny to see how her right-minded cousin had gradually lost all sense of the impropriety and error of his behavior. Almost as distressing, was the sight of Henry Crawford and her cousin Maria, in their own repeated rehearsals. Their mutual attraction was so strong that Maria hardly bothered to conceal it from her affianced Mr. Rushworth; and Mary Crawford drolly called them “those indefatigable rehearsers,” as they sought opportunities for hand holding, sighs and gazes as often as possible. Maria’s behavior shocked Fanny, and she pitied poor Mr. Rushworth, who went about glowering.

It was to avoid another of these scenes that she had sought her refuge above, wrapping herself well in a shawl. On entering, she noticed that her delicate geraniums looked pale and pining, with the lack of sunshine; and she opened the window for a few moments, despite her own shivers, to let in some breaths of fresh air upon their washed-out lavender faces with darker purple veined tracery. Shutting the window, she picked up a volume of poetry by Charlotte Smith, and found the title of a favorite poem:

“To a Geranium Which Flowered in the Winter

Written in Autumn.”

Miss Smith had only lately died, Fanny had read, but she must have written this poem in an autumn only two or three years back, and she had loved geraniums, as Fanny did herself. Thoughtfully she read:

Native of Afric’s arid lands,

Thou, and thy many-tinctur’d bands,

Unheeded and unvalued grew,

While Caffres crush’d beneath the sands

Thy pencill’d flowers of roseate hue.

Geraniums came from Africa, and were transplants, rather like Fanny herself, she mused, having come from the rougher environment of Portsmouth. Hardy ships came there from all over the world, from Afric’s burning shores to China, about which she was now reading in her great work by Lord Macartney. Why, her interest in the subject was even reflected in the name of her “East” Room. And, like the flowers, she now lived a kind of hothouse life.

She loved the delicious description – “pencill’d flowers of roseate hue.” Geraniums exactly, and she bent and looked down into the face of one sweet blossom with etched lines as its features.

But our cold northern sky beneath,

For thee attemper’d zephyrs breathe,

And art supplies the tepid dew,

That feeds, in many a glowing wreath,

Thy lovely flowers of roseate hue.

No wonder the geraniums liked the little breath of cold air she gave it from the window, to revify and strengthen it. Perhaps she too inhaled a breeze of mental strength by ministering to her geraniums – or if not, at least she gained in serenity.

It was curious how, while native plants repined in colder weather, her little geraniums flourished and flowered in October and November, despite their evident frailty and fragility, actually proving stronger than other flowers.

Again Fanny wondered – was this an analogy that could apply to herself? She was frail and delicate, a humble, modest thing, but would she struggle and endure, and thrive in the end? With a sigh, she picked up the volume again.

Oh then, amidst the wintry gloom,

Those flowers shall dress my cottage room,

Like friends in adverse fortune true;

And soothe me with their roseate bloom,

And downy leaves of vernal hue.

It was such a beautiful, perfect description of how the little flowers did dress up her room, and soothed her, that Fanny felt she loved Charlotte Smith as well as the geraniums. As often, her wondering strain gave her something to think about, and she let the delicious words run through her mind, thinking of their application to herself. “Only too flattering to be true,” she thought. “For one is not so good as the geraniums.”

She was startled from her reverie by the unusual sound of two sets of footsteps coming up her stairs. A man’s tread accompanied by a woman’s giggles. Who could it be – surely never Mr. Crawford and Maria?

To her infinite surprise, it was the two of them, arm and arm, in great high spirits. Maria knocked on the door with mock pomposity and they swept in on a gale of laughter.

“Here we are, Mr. Crawford – this is our once-hated schoolroom. No one but Fanny ever comes up here now. I am afraid it is awfully shabby.”

“And Miss Price will excuse us for the intrusion, I hope,” Mr. Crawford said politely.

Fanny did her best to assure them that it was no intrusion, and offered the small schoolgirl-sized chairs for their uncertain comfort, with apologies.

“Do not apologize,” said Mr. Crawford. “We do not mean to sit; what we do here, we can do standing. We came in search of you.”

“Of me!” exclaimed Fanny, frightened.

“To be sure,” said Maria impatiently. “You were hearing us rehearse below, but when we looked up we saw you had disappeared. We need you to prompt us, you know.”

Fanny was concerned. That her cousin and their guest should have climbed up all these steps, in search of her! She had been derelict in her duty, she should not have escaped, thinking only of herself. “Oh then, I will come down at once,” she said hastily, and was starting for the door when Mr. Crawford stopped her.

“By no means, we do not want to disturb your comfort, Miss Price. You sit here, in your own window seat, as you were doing, and only hear us run through this scene once, will you? I am sure you will be very kind and do that?”

Fanny could not refuse, and seated herself by the geraniums, with her shawl. Her visitors struck a theatrical position, and resumed the scene that they had rehearsed most.

Frederick: “It is a very hot day – a drop of wine would not be amiss. But first let me consult my purse…But who is that? A poor sick woman. She don’t beg, but her appearance makes me think she is in want…Take this, good woman.”

Agatha (stretches out her hand, and cries out with astonishment and joy): “Frederick!”

Frederick: (with amazement and grief) “Mother! For God’s sake what is this? How do I find my mother thus? Speak!”

Agatha: “I cannot speak, my dear son!” (Rising and embracing him) “My dear Frederick! The joy is too great!”

Frederick: “Dear Mother, compose yourself!” (Leans her head against his breast)

No more words came from the actors, though they continued to embrace. Fanny waited for quite some minutes, in increasing embarrassment. At last she said, “I believe, Mr. Crawford, you are to say ‘How she trembles! She is fainting,’ and Maria, you say that you are so weak and giddy – “

The two lovers laughed good-naturedly. “To be sure,” said Mr. Crawford, “you will do a very pretty faint, Miss Bertram. But, Miss Price, I am concerned – we have really been very unthinking and inattentive by you. You look quite cold, sitting there in the window! Do go downstairs, and get warm. We will follow presently.”

Mr. Crawford and Miss Bertram, by Chapman

“Yes, yes,” urged Maria, “you do that, Fanny, and we will come down after we have practiced the faint on the floor.”

“Oh by no means,” said Fanny, “I cannot leave you – I am not at all cold. Or we can all go downstairs together.”

“Oh, no, Miss Price, it is not fit for you to remain and be cold. Do go down, there’s a good girl.”

“It cannot be right to leave you,” she said uncertainly.

“Fanny!” cried Maria impatiently, “do as you are bid. Do you not know that my mother has been asking for you this half hour? She wants you to read to her, by the fire. That will make you both warm and useful. She wants to hear you read from The Idler, and I see it there on your table, so take it down with you.”

“Oh, Miss Bertram, I did not know that Lady Bertram wanted me. Of course I will go. You will follow shortly?”

“Indeed we will,” Mr. Crawford assured her solemnly. As she hurried out with her book, she heard him say, “Now Maria, for the fainting scene, you lie down here on the floor, and I will take you in my arms and comfort you. My dear mother!”

“Mother, indeed!” Maria gurgled, and Fanny heard the heavy weight as Maria’s large fully formed body thumped to the floor.

“O Mother, mother!” she heard Henry cry as he bustled to embrace her prone body.

She felt it was all wrong to leave the two of them behind her, to treat her East Room to such scenes as it had never witnessed before, but she consoled herself that they would not stay long; and her first duty was to Lady Bertram.

“Oh, there you are, Fanny,” said her ladyship’s indolent voice from the sofa. “I have been wanting you to read to me. Have you brought that interesting book? Oh good, I see you have. The Idler – I do like hearing about people who idle instead of those who always run about doing too much. And that man is so interesting. He does not hurry his words. What is his name, Fanny?”

“It is Samuel Johnson, you know, ma’am.”

“Oh, yes, to be sure. And what story will you read to me today?”

“Well,” said Fanny, seating herself upon the sofa and opening the book, “let us see. Here – how would his essay ‘On Sleep’ do?”

“Oh, that sounds most excellent,” said Lady Bertram. “I do love sleep.”

“Sleep is a state in which a great part of every life is passed. No animal has been yet discovered, whose existence is not varied with intervals of insensibility; and some late philosophers have extended the empire of sleep over the vegetable world,” read Fanny.

But Lady Bertram was already snoring.

Note: The flower photographs may or may not be geraniums, but at least they have the merit of being my property and requiring no permissions to use!

6 comments

Skip to comment form

A sweet story.

Author

Thank you very kindly, Ellen!

Diana, that was lovely!

Thank you, Susan – much appreciated!

Loved the story, Diana. Do you remember the JASNA actors theater play we “acted” together in Tucson years ago? My husband Perry was also in the cast.

Thanks for reading, Carole! And yes I remember Tucson, quite awhile ago now, but so much fun. I’m still doing Austen plays! Best regards to you and Perry.