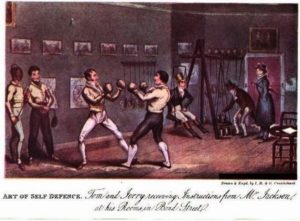

Gentlemen training at Jackson’s

“A gentleman only uses his hands to defend himself, and not to attack; we call the pugilistic art, for that reason, the noble science of defence.” Bill Richmond

If you’ve read Georgette Heyer’s Regency novels, or Regency novels in general, you’ll recognize a situation where the heroine arrives at an inn only to find all the rooms taken because of a local ‘mill’ or possibly a cockfight. Because both were technically ‘illegal’, they were held outside towns and cities. The time would be announced ahead of time and hundreds of people, many of them aristocratic young men, would appear in their barouches and shining carriages to attend the events. In my novel The Other Mr. Darcy, Caroline Bingley encounters such a problem when she arrives in Stamford, on her way to Pemberley.

In the absence of team sports [except for gentlemanly sports such as cricket], pugilism, or bare-knuckle fighting, was the most popular sport in the later Georgian extending until the mid-19th century, with specialist sports writers like Pierce Egan publishing accounts of the matches in great detail in the newspapers. The Prince of Wales attended many ‘mills’, along with many famous gentlemen of the time, among them several of the Romantic poets like Lord Byron.

But boxing was not just a spectator sport. Surprisingly, along with fencing, it was considered part of a gentleman’s education. In an age when dueling was still tied to the concept of honor — even if it had been made illegal — and gentlemen needed to defend themselves against footpads and thieves, being able to fight was still an important skill for self-defense. One of the most prominent academies for fencing was ‘Gentleman’ John Jackson’s. Some of the most distinctive members of Jackson’s were the Duke of York, the Duke of Hamilton and the Prince of Wales himself.

Jackson’s Rooms in Old Bond Street … were actually part of a fencing academy that had been run for thirty years by the D’Angelo family. Harry D’Angelo was fencing “professor” to a significant portion of the aristocracy, many of whom knew him from their Eton and Cambridge days. Jackson shared D’Angelo’s views on the character-forming nature of combat sports and his aim of promoting gentlemanly behavior in sport. The academy’s gentlemen pupils were encouraged to practice with the foils one day and take a turn with the mufflers the next (Brailsford 1988, 70-71). [i]

We know from his diary that the poet Lord Byron took regular boxing lessons there, and that he considered boxing a sport that developed both the body and the mind, a widespread concept at the time. Byron owned an elaborate wooden screen that was painted with boxing figures.[ii]

Although amateur boxing was a gentlemanly sport, as is the case in many sports today, professional bare-knuckle boxing was an opportunity for minorities to gain respect and prominence in society. Fortunes were won and lost as gentlemen bet on pugilists who became prominent celebrities and mixed with the upper classes in London.

Bill Richmond from a Portrait by Hillman 1812

Three minority boxers of the Georgian/Regency period reached almost legendary status, not only changing the sport by inventing new technical skills, but through their writings and teaching. The most prominent among these was Bill Richmond, who was so well-regarded that he was the only Black gentleman to attend the coronation of the Prince Regent (George VI) at Westminster in 1821. Remarkably, Richmond did not reach the pinnacle of his career until he was in his 40s, when his pioneering new style caught the attention of the ‘Fancy,’ and gentlemen flocked to see him in the thousands.

Richmond trained many amateur boxers in his ‘pugilistic science,’ including Lord Byron and William Hazlett,[iii] and opened his own academy in the 1820s. Bill was well educated and was frequently described as witty and knowledgeable.

Daniel Mendoza

The second minority boxing star was Daniel Mendoza, a boxer of Spanish-Jewish origin. Mendoza was rather small, and boxing at the time did not have separate categories, but he adapted the sport to suit his less bulky frame by moving and ducking. At first, this defensive style was considered ungentlemanly and cowardly, but eventually it became established as the norm. Mendoza published a popular instruction book, The Art of Boxing in 1789, and then opened his own boxing school in the Strand in 1791.

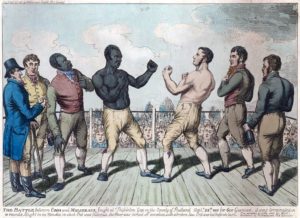

The third was Tom Molineaux (also spelled Molyneux), an ex-slave from Virginia who travelled to England to become a student of Richmond’s.

The famous fight between Crabb and Molyneaux,, with Richmond coaching.

China figurine Molineaux

Recognizing Tom’s potential, Bill put aside his own career to coach the younger man. Molineaux’s career was very short in comparison to his teacher’s, and he died young, but he was famous enough for china figurines to be made of him.

When I researched fencing and duelling for Mysterious Mr. Darcy, I discovered that fencing was taught side by side with boxing. Would Mr. Darcy have known the men I have been writing about? He would very probably have encountered them. Darcy would have taken fencing lessons, since that was one of a gentlemen’s necessary accomplishments, along with riding and dancing. Unless he was unusually disinclined to practice, he would have later spent time at Gentleman Jackson’s school at number 13 Bond street when he was in Town and would have very likely trained in the pugilists’ art. Would he have been taught by Bill Richmond there? If he was good enough (and of course Mr. Darcy was good enough). Even if he did not attend any of the ‘mills,’ Darcy might well have seen Mendoza and Molineaux in one of the several boxing outlets gentlemen of the time frequented: Offley’s, Limmer’s Hotel, the Pugilistic Society or the Daffy Club, where gentlemen sang rousing songs such as ‘A-boxing we will go’ in defiance of Napoleon.

I’m going to end with a video that gives an idea of how these early superstars were able to establish themselves among elite Society, and to become teachers to gentlemen very like Mr. Darcy.

[i] Karen Downing, ‘The Gentleman Boxer Boxing, Manners, and Masculinity in Eighteenth-Century England.’ http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.897.850&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[ii] http://www.pierce-egan.co.uk/round-5-lord-byron/4533335258

[iii] For a detailed account of Richmond’s achievements, see Luke G. Williams, Richmond Unchained: the biography of the world’s first black sporting superstar, Amberley, 2015. See also his blog www.billrichmond.blogspot.co.uk.

If you would like to read more on the subject, I found these resources useful:

https://wordsworth.org.uk/blog/2016/01/22/boxing-with-byron/

John Grant, Pugilistica: The history of British boxing (goes into a lot of detail about the three athletes mentioned) https://www.gutenberg.org/files/59465/59465-h/59465-h.htm

Wikipedia: Tom Molineaux https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Molineaux

Wikipedia: Bill Richmond https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Richmond

Wikipedia: Daniel Mendoza https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Mendoza

4 comments

Skip to comment form

I love that they taught boxing alongside fencing because gentlemen needed to know how to defend themselves. When you think about it, it makes a lot of sense to not just be a Sitting Duck. Fascinating read!

Author

Thanks, Elizabeth. I agree. I can’t imagine Mr. Darcy as a Sitting Duck!

Fascinating discussion, Monica! I love getting a clearer picture of the diversity Darcy would have been exposed to in his sporting life. Thanks!

Author

I was really pleased to come across this information. It isn’t an association you would normally make. I was especially struck by how well-admired Bill Richmond was. He really was one of the first Black athletic stars!