Girl with Monkey by Rosalba Carreira

Seeing Lord Byron crossing the garden accompanied by a monkey, a fox, and two mastiffs, Mr. Darcy observed to his wife that once, they would have been astonished by such a sight.

“It would take more than that to produce such an effect these days,” she replied. “The only difference, perhaps, is that now we are rather glad to see him, than not.”

“There is a certain novelty in having a famous poet for a neighbor.”

“Almost we might say friend,” said Elizabeth. “Even though we cannot approve of all his habits, there is something truly amiable about him.”

The children ran forward to beg to see the monkey do tricks. Byron laughed. “See if you can get him to talk,” he suggested. “I have been trying for years but it’s worse than my Armenian studies.”

This delighted the children and kept them thoroughly occupied while their parents called for some tea for their guest.

Lord Byron looked wistfully at the covered teapot and the assortment of biscuits. “Your sojourn here has not made you lose your English ways,” he observed. “It is an odd thing. In my exile, I usually am at enormous pains to avoid English travellers, but somehow you make even me think of home, in a kindly way.”

Elizabeth made him a little bow, and passed him the plate of crumpets, and the butter. “But what is so odious to you, about the English?”

“Why, they are everywhere now, since the war is over, always exclaiming about the views in most inane terms. I have heard one woman refer to the Alps as the most ‘rural’ place she ever saw. Endless pin pricks, but they are nothing compared to what they say about me.”

Darcy looked thoughtfully at the fox. “Well, you do behave differently from most of our countrymen, and any thing out of the way always attracts attention.”

“It is not that. The English, to do them justice, admire eccentricity, which has accounted in some part for my popularity, I suppose; but then they twist facts and make scandal to bring a man down. I am sure you have heard the stories.”

“I do not credit idle gossip.”

“You are very good. I shall miss your company, you know. The most, if not the only sensible, English people I have encountered here,” he replied.

“The general run of English people are too sensible to venture this far, I think,” Elizabeth replied. “I confess I do dread crossing the Alps myself, on our return home.”

“No need for that, Mrs. Darcy. The roads and conditions are so much improved even since I crossed them last, back in eighteen sixteen. Have you planned your route? Let me hear, perhaps I can advise. You might make my place at Este your first stop, then continue to Milan, and make your way to the crossing at Mont Cenis.”

“That’s well thought of,” and the gentlemen fell to discussing maps and routes very earnestly.

“You can change at Turin from carriages to the charabancs that will take you over the Alps, and then you can order new carriages to take you to Geneva. It should be quite safe for the children, and the lakes are worth seeing, before you make your way into France.”

“We thought so. I am hoping we shall see Dover after no more than six weeks’ journey, and be back in England before winter.”

“You should be safe. It is only September.”

“I am grateful that you gentlemen have planned it all so well,” said Elizabeth, “but it seems to me you have omitted the most important consideration, for all our comfort.”

“And what is that?” her husband asked anxiously.

“Why, the disposition of the carriages. You won’t want to be in one with Wickham, you know, and Lady Catherine can endure me very little better than she can Lydia. And then, I would rather be hung than spend weeks shut up in a carriage with Mr. Collins. You could not endure it yourself.”

Lord Byron threw back his head and laughed. “What a picture you paint. That is rich. All you need is for me to loan you my pet eagle, a peacock or two, and a cat, to make the company perfect!”

“We may divert ourselves during the journey, by trying to decide which animal corresponds with each traveler,” said Elizabeth archly. “My husband might be the eagle, and we have several candidates for peacock. But this is not tending to make the journey any more endurable.”

Little George hurried up to Lord Byron at this, and said earnestly, “The monkey did say something – I heard him!”

Lord Byron feigned astonishment. “No! Did he really? And what did he say?”

“He asked for something to drink. I almost heard him say cappo – capuccino. I am sure he did! Look at him, you can see he means it. Can we get some for Jocko, mama?”

“It would not be good for him, however. He does not know what he is saying. I assure you he would vastly prefer milk.”

“But he did not say milk,” said the child doubtfully.

“It is what he meant, though, and he will like it if you bring him a dish of it.”

The child pattered away, while the adults indulged in a general smile, and after a moment Darcy resumed the travel topic.

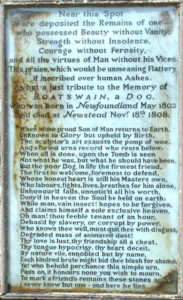

Lord Byron’s Ode to his dog Boatswain

“You do not do me justice, my dear. I have given the matter of the carriages due thought. The Wickhams will start out first, and travel by stage most of the way, with the least cost to us. He is all eagerness to get to England to take up his post, and will not object to stopping at Longbourn to wait until Lady Catherine settles the arrangements concerning him.”

“Very judicious, disposing of Wickhham like that. But then are we to have the pleasure of your aunt’s company all the way from Italy to Calais? I did not bargain on that when we married. That is too high a tax on Pemberley.”

“Have no fear. Lady Catherine mentioned to me yesterday that she means to travel by sea, and go around that say, as she believes it is easier. Mr. Collins has agreed to be her escort, and they mean to embark tomorrow sennight.”

“How admirably planned, certainly! But what to us, my love, and the children?”

“We should travel in some comfort, now that the danger of the heats are over. As my Lord Byron suggests, a few days at Este, to the Simplon pass, down to Geneva to see the lakes, and onwards to Paris. We shall take a pair of manservants, the children’s nurse and the cook, and may expect to be back at Pemberley in October, you shall see.”

“We will need a week at least to pack, I must see to what is left of my clothes after Lydia has finished with them.”

“You shall have all the time you need, my dear, and plenty of peace and calm once our relations have departed.”

“As you need not leave at once, Darcy,” said Byron, “perhaps you and Mrs. Darcy will have a little time to see any of the sights of Venice that you may have missed?”

“We have seen more than we thought possible,” Darcy replied, “I do believe there is not a Venetian stone unturned, and we have visited museums, art collections, churches and palazzi in such abundance and variety that we are longing only to subside into our own quiet countryside.”

“I thought you might feel that way. However, might you not still enjoy an excursion to the Lido one day? I do not believe that you have seen it, and there is nothing more glorious than a horseback ride on its wild sands. Shelley and I had many such rides, and I think you would enjoy the adventure.”

“Why, I am sure I should. But my wife is no rider.”

“Perhaps, but I have observed she is a walker, and the Lido, though mostly uninhabited, has some sights worth seeing. The old church – the Jewish cemetery – the octagonal island defenses. Such history, too.”

“I should like to make that our last Venetian excursion,” exclaimed Elizabeth. “Can it be managed?”

“You leave it to me. We will take my gondola, with Contessa Guiccioli as a pleasant companion for you, Mrs. Darcy, and you shall have a sightseeing walk while we amuse ourselves with our horses, and then a regular pic-nic upon the sands.”

“That is very kind of you, Byron,” said Darcy. “My wife and I accept with pleasure.”

“Only imagine. No Lydia. No Wickham,” sighed Elizabeth dreamily.

“And we can do it the very day after Lady Catherine’s departure, if you like.”

“That will be quite perfect,” said Elizabeth, her eyes sparkling.

4 comments

Skip to comment form

Oh my! Perfect planning indeed! Let’s hope it does all go to plan 🙏 I particularly like the idea of the Wickhams ravelling by stage rather than in luxury, with luck the Darcys won’t see them again 🤞🏻 or Lady Catherine and her minion? They might miss the talking monkey but I do think they will be pleased to be back at Pemberley 🥰🥰

I am enjoying the book. Only now, I have the time to follow the book. Would like to watch on netflik, not sure if hubby would watch it.

Thank you for putting on google.

I am late coming to my email. Off in San Antonio for T’Giving. This is a delightful post – no Lydia, Wickham, Collins or Lady CAtherine. I hope to read of the trip to the Lido.

Thanks for another delightful chapter, Diana! I’m glad the Darcys will get a break from their least likable relations!