Is Caroline Bingley green with envy as she notices Mr. Darcy’s attentions to Elizabeth Bennet? Does Emma Woodhouse wish unspeakable horrors on Harriet Smith because of Harriet’s crush on Mr. Knightley? After Willoughby, does Marianne covet Elinor’s more sensible behaviour? We could go on for ages, but it’s only for this month so don’t miss a post!

What does jealous lead to? Oftentimes it’s broken hearts! This is doubly true when marriage is still largely a business transaction and even the promise to marry regarded an enforceable contract. A breach of promise suit a could arise out of a broken engagement. Infringement on another man’s marriage ‘property’ could result in even more spectacular court cases and the award of greater damages.

History

As early as the fifteenth century, English ecclesiastical courts equated a promise to marry with a legal marriage. By the 1600’s, this became part of common law; a contract claim one party could make upon another in civil court suits. (And you thought this was just the stuff of modern daytime television!)

To succeed in such a suit, the plaintiff, usually a woman, had to prove a promise to marry (or in some cases, the clear intention to offer such a promise), that the defendant breached the promise (or the implied promise to promise), and that the plaintiff suffered injury due to the broken promise (or failure to make the implied promise. Don’t think about it too hard, it’ll make your head hurt.) Marianne Dashwood of Sense and Sensibility would likely have had grounds for such a suit against Willoughby if she want, and could afford the legal fees.

Breach of Promise claims

A breach of promise suit required a valid betrothal. Promises to marry when both parties were below the age of consent were not valid. Similarly, promises to marry made when one was already married (as in I’ll marry you if/when my current spouse dies—how romantic!) or between those who could not legally marry were not enforceable.

A breach of promise suit required a valid betrothal. Promises to marry when both parties were below the age of consent were not valid. Similarly, promises to marry made when one was already married (as in I’ll marry you if/when my current spouse dies—how romantic!) or between those who could not legally marry were not enforceable.

If significant and material facts were discovered that could have influenced the agreement, then betrothal could be dissolved without penalty. So issues like misrepresentation of one’s financial state, character, mental or physical capacity presented valid reasons to end an engagement.

If a betrothal was valid, a breach of promise claim could be presented in court.

Reasoning

Why were such claims filed when it seems like it would be far easier, less painful and less embarrassing for a couple to simply go their separate ways? When a promise to marry was broken, the rejected party, usually female, suffered both social and economic losses.

Socially, an engaged couple was expected to act like an engaged couple. Though it seems unfair in modern eyes, the acceptable behaviors she may have shared with her betrothed, would leave her reputation damaged if he left her. Moreover, though premarital sex was officially frowned upon, it was known that a woman was much more likely to give up her virginity under a promise to marry. But if that promise was not kept, her future search for a husband would be significantly hampered for having broken the code of maidenly modesty.

The loss of reputation translated to serious economic losses, since middle and upper class women did not work outside the home and required a household supported by a husband’s wealth. A woman with a tarnished reputation was unlikely to marry well.

Damage Awards

Perhaps as a result, a woman was far more likely to win a breach of promise claim than lose one. Middle-class ladies were generally able to obtained larger damage awards than working women, though cases varied greatly. About half of women winning damages obtained £50 – £200. (For reference, middle class family of four could live comfortably on £250 a year.)

While these awards could indeed offer assistance to wronged plaintiffs, the system was also ripe for abuse. Jurors were often unduly sympathetic toward jilted women, especially when they were attractive or portrayed as particularly virtuous. Damage awards could easily be swayed by such sympathies, making false claims very tempting. If all this sounds much like modern reality television, criminal conversation cases resemble it even more.

Criminal Conversation

During the late Georgian era, in England, sleeping with another man’s wife was not a legal offense. (Interestingly, it was in Scotland, though.) However a little detail like that could not stop cuckolded husbands from taking their wives’ adulterous lovers to court.

During the late Georgian era, in England, sleeping with another man’s wife was not a legal offense. (Interestingly, it was in Scotland, though.) However a little detail like that could not stop cuckolded husbands from taking their wives’ adulterous lovers to court.

Since dueling over offenses of honor was increasingly frowned upon, gentlemen sought reparations in civil court. Civil laws concerning trespassing also addressed issues of ‘wounding another man’s property’. Since a wife was by law, effectively chattel, a husband suffered damage to her chastity when adultery occurred, thus entitling him to financial compensation under civil law. If she ran off with her lover, the husband could also claim damages for the loss of her services as household manager. Rushworth of Mansfield Park could have brought such a case against Henry Crawford over Maria’s transgressions.

The euphemistic name for the offense was Criminal Conversation (Crim Con).

If a husband had evidence of adultery, he could launch a civil crim con case against the other man. Thus, he might vindicate his own honor and destroy his rivals character and finances, all without the unsavory shedding of blood.

Interestingly, the wife however was not a party to the suit. (Remember the whole being property thing? That.)

Criminal Conversation trials

The last decade of the 18th century was by far the heyday for the crim con trial. Lord Chief Justice Lloyd Kenyon declared that the country was in the grip of a “crisis of morality”. (Fullerton, 2004) Only after the average award settlements dropped in the early 19th century did the number of claims begin to decline. Wonder if there’s a connection…

In any case, crim con trials tended to be colorful, highly publicized events at the Court of the King’s Bench, in a corner of Westminster Hall. Though ‘reality tv’ was not yet a ‘thing’, these trials were open to the general public. And for those not fortunate enough to be able to attend in person, most book sellers carried newspaper, pamphlets, transcripts and ‘true’ exposés documenting all the sexual misadventures of high society.

In any case, crim con trials tended to be colorful, highly publicized events at the Court of the King’s Bench, in a corner of Westminster Hall. Though ‘reality tv’ was not yet a ‘thing’, these trials were open to the general public. And for those not fortunate enough to be able to attend in person, most book sellers carried newspaper, pamphlets, transcripts and ‘true’ exposés documenting all the sexual misadventures of high society.

Lawyers on both sides of the case played up the cases’ drama as much for the public notoriety as for the effect on the court’s decisions. They called servants, especially young pretty ones, to deliver testimony for both the plaintiff and the defense. While servants could be (mostly) excused for presenting salacious tales in similar language, the barristers were gentlemen and adopted notable euphemistic and flowery language to express the necessary elements with decency and taste. Some said it became something of an art form.

With so much at stake, both in terms of finances and reputations, truth and accuracy fell to the need to convince jurors.

The defendant, if he could not deny that he had seduced the plaintiff’s wife, was obliged to present the object of his attentions as a low, debauched, corrupted woman who was worthless to the world let alone her sorry husband. The plaintiff, in order to secure a high payout, had to present his marriage as an unending festival of joyous love and his unfaithful wife as the best and most innocent woman in the world before the wicked seducer got his grubby hands on her. (Wilson, 2007)

As a rule, these trials progressed quickly and once damages were assessed, they were enforceable like any other debt.

Damage Awards

In deciding damages, the jury had several factors to consider. The rank and fortune of the parties helped determine the loss the husband had suffered, effectively setting a cash value of the wife before her seduction. Juries also weighed the length of the marriage and the affair, whether the two men were friends before the seduction, and whether or not said seduction had taken place in the marital bed (an ever greater outrage and offense.) Often, juries wanted to insure that the well-heeled rake was sufficiently punished to deter more of his kind from following in his footsteps.

Juries often awarded only half the damages requested, so indignant gentlemen just increased the amount they asked for, often sums totaling over £15,000. Occasional cases were settled for up to £20,000 but awards of at least £1,500 were far more common.

Ironically, it was not unusual for a married couple to remain married after the conclusion of a crim con case. However, such a case was a preliminary step in divorce proceedings.

Crim con and divorce

By the end of the 18th century, the House of Lords decreed that a husband must have brought a successful case for damages against the adulterer for criminal conversation with his wife before it would agree to consider a divorce bill. At this period the only means of obtaining a divorce that would permit remarriage was by private Act of Parliament, usually preceded by a trial for criminal conversation which would prove in court the guilt of the party to be divorced – who, as the law then stood, could only be the wife.

Reference

Fullerton, Susannah – Jane Austen & Crime JASA Press (2004)

Wilson, Ben – The Making of Victorian Values, Decency & Dissent in Britain: 1789-1837 The Penguin Press (2007)

Breach of Promise to Marry Research – Facts and Figures Denise Bates http://www.denisebates.co.uk/bopfacts.html

Breach of Promise to Marry Research – New Discoveries Denise Bates http://www.denisebates.co.uk/bopdiscoveries.html

13 comments

Skip to comment form

This is a well-researched and presented piece of background! Thank you, Maria Grace for providing some education that I hadn’t realized how much I needed.

Author

Thanks, Katherine. Some of this surprised me too.

Very interesting. Thank you for shaing the historical research.

Author

Thanks, Deborah!

When we moved to Texas in 1969 as my husband was to be stationed at Ft. Hood, I learned from co-workers that in Texas it was considered justifiable homicide if a spouse walked in on the other spouse committing adultery and murdered…but I can’t remember if it was one or both of the participants.

Looked it up on the Internet: “In Texas until 1974, a husband who killed a wife and her lover when he caught them in flagrante delicto was not judged a criminal. In fact, the law held that a “reasonable man” would respond to such extreme provocation with acts of violence.”

Doesn’t say the wife could shot her husband for the same thing, though.

Author

I’ve spent almost my entire life in Texas, and that sounds entirely like the state. LOL I don’t know if it would apply to the wife, but Texas being what it is, I think there’s a good chance of it! Thanks Sheila!

Very interesting!! Thanks, Maria!

Warmly,

Susanne 🙂

Thanks for another of your interesting reviews of social customs.

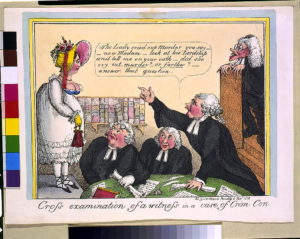

Can you give us the sources for your illustrations?? That first painting looks intriguing.

Author

They can all be found on wikimedia.

Eduard Swoboda. (Vienna 1814-1902 Hallstatt) The Spurned Bride;

Title: Trial of the Rev. Edward Irving, M.A.; a cento of criticism, 1823;https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trial_of_the_Rev._Edward_Irving,_M.A;_a_cento_of_criticism_(1823)_(14579280930).jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crim._con_LCCN2003652528.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cross_examination_of_a_witness_in_a_case_of_crim_con_LCCN94504605.jpg

A fascinating topic. Thanks, Maria.

I did some research on breach of promise, several years ago while writing “For Myself Alone.” The most surprising thing I discovered is that early on in the history of the phenomenon, men were as likely as women to file these suits. A man didn’t risk so much in reputation by a broken engagement. But it goes back to what you said about marriage at the time being very much a business arrangement. If a woman with money had promised to marry a man who needed it, he could be seen as injured if she changed her mind – injured financially by losing the fortune he expected to acquire from his future wife. He might even have borrowed against his “expectations” and be left in debt when she withdrew. Public opinion gradually turned, though, and made this form of recourse less and less popular until it became what most people are familiar with – almost exclusively women suing men.

Superb article and very interesting. I thought about Sir Thomas Bertram offering to speak for his daughter Maria and end her engagement with Mr Rushworth after his return from Antigua. He had rightly seen that her behavior towards her fiance was cool and even dismissive and he had realised that Mr Rushworth was limited in intelligence and education. That would have been a breach of promise but one that would not have hurt either party materially. It would have been a scandal but one Sir Thomas felt could be weathered. Possibly if Sir Thomas had also suggested that Maria go to London and stay with her cousins or even sent her to london, good lodgings, with Mrs Norris in attendance, she might have accepted his offer to release her from her engagement.Or go to Bath. Anyway, I also thought of Captain Wentworth, who did not seem to realize until Louisa’s accident, that the people around them considered them semi engaged. Being an honorable man, this caused him to atleast not pursue Anne until Louisa’s situation had changed.

Fascinating research! Soap opera indeed! I am surprised they went through quickly though as I thought the courts were so backlogged even then. Thank you!

Your research is always so thorough and interesting. Thank you.