The sad day is come: the day when people all over the world cannot help but give a thought to Jane Austen, who died two hundred years ago. Tributes there will be in plenty; a few dissenters may proudly squawk that they never read her because they have better things to do. (Their loss.) Most will wish, however, that she might have lived another forty-one years in the world to delight us even more than she did, if that were possible.

As she herself wrote, trying to console herself about her illness, “If I live to be an old Woman I must expect to wish I had died now, blessed by the tenderness of such a Family & before I had survived either them or their affection.”

As she herself wrote, trying to console herself about her illness, “If I live to be an old Woman I must expect to wish I had died now, blessed by the tenderness of such a Family & before I had survived either them or their affection.”

As we now know, she did not outlive the affection of posterity; we, strangers to her, still mourn her sadly early death, and regret the books she had not time to write. Did she ever imagine such a thing? She once had Elizabeth Bennet say playfully to Darcy that they were both “unwilling to speak, unless we expect to say something that will amaze the whole room, and be handed down to posterity with all the eclat of a proverb.” Well, hand down her words Austen did, and a thousandfold more than a proverb. Her eclat, her whole work, are in no danger of being forgotten.

Jane Austen evidently faced her death with realism and fortitude, despite suffering. “In that hour was her struggle, poor soul,” Cassandra wrote poignantly, adding that when she asked if she wanted anything, her sister starkly replied, “Nothing but death.” She had, with her philosophy, her religion, her sense, reached that final resignation. Yet how she looked on death when she was still personally comfortably far from it, was something quite different. On seeking for examples in her writing, we often find her positively laughing at death.

In Pride and Prejudice, her most blithe and comic novel, references to death are humorous, as when Mrs. Bennet hates “to think that Charlotte Lucas should ever be mistress of this house, that I should be forced to make way for her, and live to see her take my place in it!” Mr. Bennet replies: “My dear, do not give way to such gloomy thoughts. Let us hope for better things. Let us flatter ourselves that I may be the survivor.” The narrator adds, “This was not very consoling to Mrs. Bennet.”

Sense and Sensibility opens with a death, and the wise and witty pronouncement: “The old Gentleman died; his will was read, and like almost every other will, gave as much disappointment as pleasure.” The ensuing scenes, though solemn in subject and treating of the dire circumstances in which the Dashwoods are left, are among the most horrifically hilarious that Austen ever wrote, as John Dashwood’s wife easily talks him out of his first inclination to provide for his sisters. Although written early in her career, this is certainly Jane Austen at her most cynical, in the strain that made Auden write about how shocking it was to hear her describe the effects of “brass.”

Another death in Sense and Sensibility is Col. Brandon’s harrowing story of his lost love Eliza falling into sin and dying of consumption. This is narrated almost melodramatically, with the conclusion, “Life could do nothing for her, beyond giving time for a better preparation for death; and that was given.” This short account is a rare look into piteous tragedy and Austen does not dwell long on it, using it for her own ends in creating sympathy for Brandon. Still, the narrative remark gives a glimpse of her belief that death is something to be “prepared” for.

Although Mansfield Park has some claim to be Austen’s darkest novel, its deaths are but two, and briskly dispatched, with no sentiment whatever. Fanny’s little sister Mary had died while she was at Mansfield, and on hearing about it she had “for a short time been quite afflicted.” Fanny’s mother takes up the tale, and Austen uses this to reveal her character with its ill-judging sentimentality, as she says about Mary’s death: “Poor little soul! she could but just speak to be heard, and she said so prettily, ‘Let sister Susan have my knife, mama, when I am dead and buried.’…Poor little sweet creature! Well, she was taken away from evil to come.” These pieties sound bland, but are jarringly effective, when spoken amidst the utter chaos, both mental and physical, in which Mrs. Price lives.

The second death in Mansfield Park is that of Dr. Grant, and it is a straightforward plot device without any pretense of feeling or regret, practically provided to give Fanny and Edmund the parsonage house they want and need after their marriage.

In Emma, the death of “the great Mrs. Churchill” is similarly a plot device, with the addition of a few satiric observations on the subject of what happens when a disliked person dies:

“Mrs. Churchill, after being disliked at least twenty-five years, was now spoken of with compassionate allowances. In one point she was fully justified. She had never been admitted before to be seriously ill. The event acquitted her of all the fancifulness, and all the selfishness of imaginary complaints.”

There are no real deaths in Northanger Abbey, but the over-active imagination of Catherine Morland is capable of summoning up fanciful ones. In full comedic strain, yet gently, Henry chastises her for imagining that his own father murdered his mother, and assures her that all the proprieties were in fact observed about her death:

“If I understand you rightly, you had formed a surmise of such horror as I have hardly words to — Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions you have entertained. What have you been judging from? Remember the country and the age in which we live.”

Perhaps the most unfeeling death in the novels is that of poor Dick Musgrove, in Persuasion, which Jane Austen describes by saying that “the Musgroves had had the ill fortune of a very troublesome, hopeless son, and the good fortune to lose him before he reached his twentieth year.” The scene reveals what Captain Wentworth’s duties were to such a sailor, and also that he could be compassionate toward the boy’s mother, showing the “self-command with which he attended to her large fat sighings over the destiny of a son, whom alive nobody had cared for.” Here the apparent callousness over the death of a young man, and the “fat-shaming” as we would call it today, are both uncomfortable to modern ears; but they formed part of Austen’s contemporary attitudes toward death and the sentimentality that in her view often attended it.

So Jane Austen touched on death in her novels in different ways: alluding to it mainly for the sake of plot devices and jokes of the skewering kind. This trait is more pronounced in her Juvenilia, where the gay and outrageous jokes of her youth are not yet toned down from fever pitch. In the Letters there is greater range in her allusions to death, from cruel wit of the Dick Musgrove type (famously “Mrs. Hall, of Sherborne, was brought to bed yesterday of a dead child, some weeks before she expected, owing to a fright. I suppose she happened unawares to look at her husband”), all the way to Austen’s grave, sincere letters announcing her father’s death, in which she says (and presumably feels) “everything she ought.”

Seldom does Austen specifically allude to facing death, the fear of death, preparation for death, all the things she may have been feeling in the weeks leading up to the sad date two hundred years ago. She does dryly mention, in Emma, that “the only mental provision [Harriet] was making for the evening of life, was the collecting and transcribing all the riddles of every sort that she could meet with.” Her own provisions, we feel, were different.

Jane Austen’s letters show her surrounded by life: her family, her work, trips, domesticity, and news make for crowded busy letters. But she was equally surrounded by death, to a far greater degree than is usual today. Without listing the catalogue of deaths that touched her, there were plenty: two sisters-in-law and many more women in her circle died in childbirth, and she shows her complete awareness and sensitivity to such circumstances when she writes, “I believe I never told you that Mrs Coulthard and Ann, late of Manydown, are both dead, and both died in childbed. We have not regaled Mary [her brother James’s pregnant wife] with the news.”

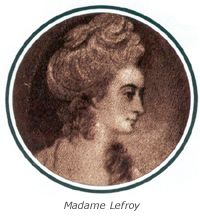

Jane Austen presents, as perhaps many of us do, a kind of separation of mental compartments in dealing with death. There are the polite conventional things to say and rituals to follow; there is practical speculation about the social matters attendant on death, such as legacies and mourning costume; and there is grief, conducted as far as possible behind closed doors with the decent constraint of privacy. Occasionally there are glimpses of such griefs in her fiction, as when the young Anne Elliot goes unhappy to school after her mother’s death. It is rare that we see anything of Jane Austen’s own mind in deep grief, but it is shown in the poem she wrote four years after the death of her good friend Mrs. Lefroy, who had died on her birthday, December 16, 1804.

“The day, commemorative of my birth

“The day, commemorative of my birth

Bestowing Life and Light and Hope on me,

Brings back the hour which was thy last on Earth.

Oh! bitter pang of torturing Memory!—

And with the heartbreaking line, “Let me behold her as she used to be.”

Her sincere Christianity is inevitably evoked in such a case, and she writes,

“Oh! might I hope to equal Bliss to go!

To meet thee Angel! in thy future home!—“

How Jane Austen felt about her own mortality, we can only guess; and we must suspect she would have preferred that we not try. Yet she confounds speculations about either her despair or her prayers, by writing a rather menacingly jocular poem about the Winchester Races, and the fury of St. Swithin, on her very deathbed, only two days before the end. About the actual end itself we know enough, thanks to Cassandra’s beautiful account of the event and her own feelings. We think about this letter, and the loss to her family, the world, and to herself, on the important anniversary; but as well we can remember what Jane Austen had in truth been preparing for, and what she alludes to in that final poem: immortality.

“When once we are buried you think we are gone/ But behold me immortal!”

St. Swithun

27 comments

Skip to comment form

Such a lovely tribute. Thank you!

Author

Thank you, Bonnie!

Thank you for such a lovely tribute to our dear Jane.

Author

Thank you, Mary!

What a lovely tribute. Thank you.

Author

Thanks, Shelley!

Thank you for this thoughtful and appropriate post. I sometimes wonder if her comment ‘Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery’ was one of her reasons for not writing more about death in her books. It was such a constant in her life.

Author

I think you are right, Carole, I’ve had the same thought about that quote. She made the decision not to dwell on death – she was so interested in men and women, and living.

Beautiful post.

What a lovely tribute. Thank you!

Author

Thanks, Lorna!

A fitting tribute!! Thank you, Diana!

Warmly,

Susanne 🙂

Author

Glad you thought so, Susanne!

Beautifully written. Thank you.

Author

Thanks, Helen.

A beautiful memorial to a favorite author. Thank you for writing this Diana.

Author

Appreciate your saying so, Deborah!

Thank you for this thoughtful tribute, Diana. Perhaps there was enough death around her in everyday life that she might not have wished to dwell on grief and misery in her novels.

Author

That makes sense to me, Abigail. Glad I had the chance to do this…

What a lovely tribute to our dear Jane.

Author

Thank you, Carol.

Very nice tribute, Diana. Jane had a rapier wit and a way with words. In a letter to Cassandra January 1799, she referred obliquely to her death. ‘You express so little anxiety about my being murdered under Ash Park Copse by Mrs. Hulbert’s servant, that I have a great mind not to tell you whether I was or not.’ 🙂

Author

The most wonderful quote, Gianna! Thanks. Makes me fall in love with her all over again!

Thank for such a lovely tribute, Diana. I would have loved to have been in Winchester last Tuesday but was unable to make the journey, but I will be there at the end of August and will be paying my respects then.

Author

It looked like the most beautiful and emotional time, Anji, I was sorry not to be there, too. But my heart was, and my body will be there too, some time this autumn.

Sorry, I just got to this. So many e-mailed blogs recently. Yes, Jane has forever found a place in history and in our hearts. Thanks for sharing.

This is a lovely tribute. I really appreciate it.