In our Austen Variations fundraiser for Ukraine, our authors offered cameos in their forthcoming novels in exchange for donations to the cause. My first cameo was written for donor Michelle d’Arcy (a most fortuitous name to work with!), to be included in my next novel The Darcys and Lord Byron in Venice, and it was posted here on March 11.

Wisteria in Venice, courtesy of Laura Teso of the My Corner in Italy blog

Now I have a double cameo for you – two stories, about two people. The introductory story, at least, is true! Here it is. France Burke, a talented poet and sculptor, and my mother, Helen Finkelstein Reeve, were good friends when they were both students at the Dalton School in New York City in the late 1930s. My mother passed away about ten years ago, in her ninetieth year; France in 2017. I had never known about their friendship, or much about my mother’s school years. She married young, to my father Paul Eaton Reeve, a Greenwich Village poet. But after France’s death I was approached by her partner Sam Shea, who had tracked me down through my parents’ names and found a piece I had written on the Vulpes Libris book site, about my father’s poetry. Sam had been going through France’s papers, including school diaries and letters, and had found many references to my mother. References to events more than eighty years in the past! Sam graciously shared them with me, and not only was I mesmerized, I felt privileged to read the stories of how young France and “Bunny” as my mother was called, as schoolgirls in their teens, adventurously explored the cultural life of 1930s/40s New York. One of their great pleasures was going to the theater together, and it was entrancing to read about their delight in seeing the plays, films, and ballets of the day. I was particularly delighted when France noted in her diary, in 1940, “I saw ‘Pride and Prejudice’ again, and met it with the same affection. The most pleasurable movie ever invented.”

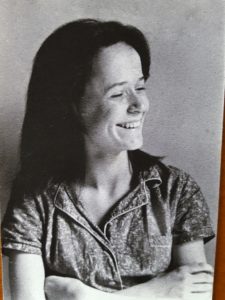

France Burke

About her friend Bunny, she wrote, “She has taken me to see ‘Pens and Pencils’ and has just given me a $2.20 seat for ‘Hamlet’ for Thursday night. She is so nice I don’t know what to do. We get along wonderfully as we laugh all the time. She is a junior and to make up for it she says “I’m as silly as a freshman and you’re as wise as a junior, so what of it.”

Helen Reeve

After my mother’s marriage the two friends drifted apart, and I don’t believe they ever saw each other after the 1940s, though France often spoke of the lively, bright artistic Bunny she remembered and how she wished she would come to a school reunion. My mother had a sad life, with depression and emotional problems, and I think felt bad about meeting her Dalton friends.

Now that I know Sam, I know France, and have deeply enjoyed reading her poetry and seeing her beautiful sculptural work, examples of which can be seen on a Facebook tribute site called “Poems Plus: The Work of France Burke.” I wish I could have known France, and I know Sam would like to have met my mother. After I wrote my first “cameo” piece, Sam offered a donation, and asked if my story could be done in memory of the friendship between France and my mother, with cameos for both of them. I felt very touched and honored, and only too glad to comply.

But – how to work two New York early twentieth century teenagers into a story about Mr. and Mrs. Fitzwilliam Darcy and their sojourn in Venice with Lord Byron, circa 1816? Talk about a writing challenge! I do not know that I have succeeded, but one thing is true: it is very much a tribute to France Burke, Helen Reeve, and their long ago friendship, and is generously dedicated by Sam Shea to the people of Ukraine.

Excerpt from The Darcys and Lord Byron in Venice

Photo courtesy of Laura Teso of the My Corner of Italy blog

“April in Venice! Yet I confess,” said Elizabeth, leaning her elbows on the balcony of the Palazzo Mocenigo, overlooking the canal, “that I am missing the English springtime, and English flowers, more keenly than I ever thought I would.”

“Flowers? Why, here are all you could wish, I should think,” said Mr. Darcy, waving his hand toward the abundant purple wisteria blossoms hanging down and covering the whole frontage of the palazzo. From their vantage point on the balcony, they were enjoying the fine spring afternoon, soft flower-scented air, and Venetian view. Elizabeth smiled at her husband. “Undoubtedly,” she said, “it is hard on the Venetian wisteria to blame it for not being primrose or crocus.”

Lydia, sprawling on the grass, never minding fresh stains on the white muslin gown, said crossly, “What do you want with flowers, any way. Here are plenty of pots, with something or other in them. Tulips.”

Lady Catherine de Bourgh, at a table sitting at as far a distance from Lydia as possible, rarely deigned to speak to her, but here she must expostulate. “Really! Such ignorance. I have always wondered at your mother’s methods with her girls, and see the result. This one does not know the difference between a tulip and an oleander.”

Lydia tossed her head. “Why should I,” she retorted. “I have something else to think of. I would like flowers well enough, if I had plenty of them to wear at the next ball, but there is nothing going on in Venice at all, and none of you ever stick your heads outside the gate. Even Meryton is livelier than this sad place. I wish I was at Brighton, of all things.”

“I see you have not lost your love of soldiers,” Lady Catherine said contemptuously.

“Not I! And I never will. I always will love a red coat. But,” she said thoughtfully, “I may change my mind. These dark and handsome gondoliers are well set up fellows, some of them. I would not mind going for a gondola ride, I can tell you that.”

Lady Catherine drew breath to launch into a lecture, but was suddenly distracted, and exclaimed instead, “Why! Here is Lord Byron. I did not expect to see him.”

Indeed, his Lordship was emerging from his own garden entrance, and approaching the Darcy party near their end of the lawn. Since he seldom intruded upon his neighbors, by mutual tacit agreement, Mr. and Mrs. Darcy were surprised, but waited calmly to see what he wanted.

He made his bow. “Mr. and Mrs. Darcy,” he said politely, “Ladies. I beg your pardon for the disturbance, but I must throw myself upon your mercy. I am in a plight that is only too common for me – I am besieged by lady visitors.”

“That is a complaint I would not expect to hear from you, Your Lordship,” said Mr. Darcy mildly, “and I would remind you that it is not according to English customs that you should mention your liaisons amongst the ladies of my family.”

“English, that is it exactly,” Byron replied. “I have complained often enough about parties of visiting English ladies, who incessantly seek me out, not for the beauty of my fair countenance, but to talk about poetry, God help me.”

“If you will write such very beautiful poetry, Lord Byron, I suppose it must be expected,” said Elizabeth dryly.

He bowed to her. “Mrs. Darcy, it is your help that I particularly entreat.”

She looked at him in astonishment, and Darcy’s face became forbidding.

“My help!” she exclaimed. “But what can I do? Do you consider me in the nature of a sort of duenna?’

Lady Catherine drew herself up. “I am the senior lady in company, I beg you to recollect, Lord Byron. Any request for advice or chaperonage ought properly to be addressed to me.”

“Suppose you tell us what has happened, Byron,” invited Darcy.

“Yes.” Byron ran his fingers through his long hair in exasperation and flung himself into a chair. “As a matter of fact, it is not English ladies who have attacked me this time, Darcy. It is Americans. Two of them.”

Darcy was astonished. “Americans! Two American ladies? I have not met any Americans in Venice.”

“There are two now,” Byron said grimly, “and I suspect them to be the verist worst samples of the outlandish bluestocking race I ever hope to meet. You positively must rescue me.”

“Is that them?” Lydia asked, pointing at two young women emerging from the door of Byron’s portion of the palazzo.

Byron looked at them without enthusiasm. “Yes, Lord help me. They have interrupted my afternoon’s work, and I tell you they are young women of a great deal of conversation. Different somehow from English girls.” He thought a moment. “You may, perhaps, find them curious specimens.”

“Do introduce us, then,” suggested Elizabeth. “If you think they are decent girls enough, we will not object, will we, Mr. Darcy.”

He shrugged. “As you wish, Elizabeth. They must be an oddity, and I will not be frightened by a pair of learned ladies. But these look quite young.”

“They are,” said Lord Byron. “Really, I ought not to have been in a temper, I just disliked the interruption. They seem to have no harm in them, and may amuse you as a novelty…Here! Miss Burke, is it, and your friend, come over here. Allow me to introduce you to my neighbors. Mr. Darcy, his wife, and her sister; his aunt, Lady Catherine de Bourgh.”

The two young women curtseyed, as the others surveyed them. They seemed to be about eighteen years old, and were of different types. Miss Burke was tall and slender, with light brown hair, plainly and simply dressed, with a look of composure and considered intelligence. Her companion was smaller, rounder, with dark skin and curling black hair, more fashionably costumed, and with a lively look. Lydia surveyed this girl’s pelisse with interest.

“Lord Byron tells us that you are Americans,” said Elizabeth civilly.

“Yes,” said Miss Burke. “My father is a literary man, and has brought the family to the Continent to do some work. We have taken a house near Palazzo Quirini Benzon in the Sestere San Marco.”

Lord Byron was surprised. “Really! You are acquainted with Signora Benzon?”

“Yes – a little,” replied Miss Burke diffidently. “Papa had letters of introduction to her, and she helped us find our house. She seems a very kind lady. Do you know her?”

Byron laughed. “Young innocent! Signora Benzon is one of the two greatest salon ladies of Venice – the only rival to Signora Abrizzi. I shuttle between one and t’other. In their rooms you will find the best literary society in Venice, as your father surely is aware. May I have the honour of knowing his name?”

“Mr. Kenneth Burke.”

“The philosopher and literary critic? Yes, his reputation is known to me, even from across the seas. And is his daughter a writer, I am almost afraid to ask?” his eyes looked both rueful and twinkling.

“Not yet, but I would like to be,” Miss Burke answered shyly. “I have tried to write poetry, and I greatly admire yours.”

“It would be immodest in me to comment upon your taste, young lady,” he told her. “And your friend – is she a writer too?”

“No; my friend paints, and her family permitted her to accompany mine from New York, to study art. We were at school together in New York, and both our families thought we would both benefit from a year or two spent in Europe.”

“A novel idea, to take such a vast journey for such purposes,” observed Darcy. “We have seen few Americans here, though now with the coming of the peace, I daresay it is only the beginning of people making such travels. Are you pleased with your experiences so far?” he addressed the smaller girl.

“Oh, yes,” she exclaimed, enthusiastically. “I never dreamed of such beauty! And France and I – “ she turned to her friend, “Miss Burke I mean; her name is France, and she is an artist as well as a poet. She sculpts.”

“And you, young lady, what is your name?” asked Mr. Darcy.

“I should have told you,” apologized France. “My friend is a Jewess. Her name is Hannah Finkelstein.”

“Oh, France, you know I am going to change it to Helen.”

“And change your last name, too, when you marry Mr. Reeve,” France agreed, and explained to Mrs. Darcy, “Bunny – that is what we called her in school – is the older of the two of us.”

“Even though I am small, I am nearly twenty,” she said brightly.

“And she is engaged to marry a poet.”

“Good God,” exclaimed Lord Byron, “Don’t do it, young lady, by all that is holy.”

“You do not speak well of your fellow poets, Lord Byron?” said Elizabeth with raised eyebrows.

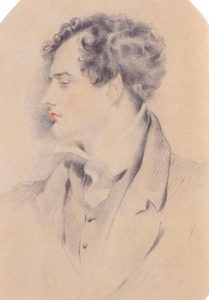

Lord Byron

He shuddered. “Any mother should lock up her daughter rather than allow her to marry one. There is no surer path to a ruined life. I know my tribe too well.”

“You frighten my friend,” said France, with concern.

“I mean to,” Byron answered seriously. “Drinking – morals such as you young innocents cannot imagine – selfishness, carelessness for the affection of others – these are all hallmarks of the men who devote themselves to poetry. I possess all of them myself, I assure you, and I know of what I speak.”

“It cannot take place for some time,” Miss Finkelstein said hastily. “Not until I am twenty-one at least. That is one of the reasons my family sent me with the Burkes to the Continent. They do not wish me to marry outside the faith.”

Paul Reeve

Her hearers were struck silent by this revelation. Mrs. Darcy searched for something to say. “Are your parents artistic people too, Miss – Miss Finkelstein?”

France answered for her. “No, her father is a professor of law, and uncle an eminent theologian. Bunny comes from a very good family.”

“I am glad to hear it,” said Byron with interest. “I have always had an immense interest in the Jewish people, as well as concern for their travails.”

“We know,” said Bunny with a grateful smile. “France and I have read your ‘Hebrew Melodies’ together, and think it wonderful. It is one of the reasons we wanted so much to meet you.”

“I am afraid we were a bit forward in pushing our way,” admitted France. “My mother and father would not have liked our coming, so I admit we acted on our own.”

“No English young lady would ever do such a thing,” Lady Catherine observed with certainty.

“We would not have done such a thing, for any body but Lord Byron,” explained Bunny.

“So, which of my Hebrew Melodies did you young ladies like best?” Lord Byron asked. “’She Walks in Beauty,’ I’ll be bound. It seems to be the favorite of females.”

“It is exquisite,” said Bunny shyly, “and I do love it perhaps partly because I am so dark myself.”

“But there are so many beautiful verses in ‘Hebrew Melodies,’ so lyrical and so high minded. I do think ‘She Walks in Beauty’ the finest, but Bunny likes ‘Oh, Weep for Those,’ don’t you?” said France.

Byron rolled off a stanza in his beautiful voice:

“Tribes of the wandering foot and weary breast,

How shall ye flee away and be at rest!

The wild-dove hath her nest, the fox his cave,

Mankind their country — Israel but the grave!”

Bunny clasped her hands. “Yes,” she breathed. “Tell me, Lord Byron, how did you come to write ‘Hebrew Melodies’ – and to know so much about my people?”

“Why, only a few poems really touch on the Hebrews, but I was asked by the composer Isaac Nathan to write lyrics for some melodies that he said dated back to the time of the Temple of Jerusalem. I know he exaggerated, well, lied; but I could not resist. That may account for their high minded tone, as you say. Even my strait laced wife had no objection to transcribing them, before I left England.”

The girls were embarrassed, as they knew there was a scandal concerning Byron, his wife, and his departure from England, even though they had never been told the whole.

“I always had sympathy for the downtrodden condition of the Jews,” he continued, “and the poems do express that, I think. I did receive some spiteful notices – one said I would become the poet of the synagogue – but on the whole they have been most popular, as evidenced by your knowledge of them so far away as America.”

“Did you like Mr. Nathan, the composer?” asked Bunny.

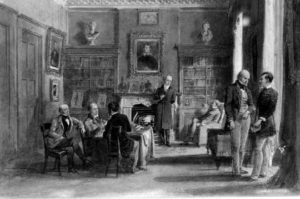

“Yes; he is well enough, perhaps not of the first rank in his talents. I must say that the person of your heritage whom I admire most, Miss Finkelstein, is Isaac D’Israeli. Do you know of his Curiosities of Literature? A great scholar, I have learned much interesting lore and information from him, and had the honour of meeting him at my publisher’s office, before leaving England. Perhaps his work is known to both your learned fathers?” he inquired.

An1815 meeting between D’Israeli, John Murray II, Sir John Barrow, George Canning, J.W. Croker, Sir Walter Scott and Lord Byron

“I believe the volume is in my father’s library,” said Bunny, “though I have not read it. What sort of Curiosities are they?”

“Oh, it is a cornucopia of subjects, positively epic. Some of them are: Literary friendships; the popes; ancient cookery; Saturnalia; the question of Adam not being the first man; and the Secret History of Authors who have Ruined their Publishers. Why, there is even an essay on the subject of the Fair Sex having no souls, in which you may be interested,” he said with a laugh.

“Good heavens!” exclaimed Elizabeth.

“Seriously, to D’Israeli, literature means knowledge, and he is bursting with more of it than any man I have ever known,” said Byron earnestly.

“I will ask my father if he knows about D’Israeli, when we get back home tonight,” said France. “Speaking of that, however, my family must not be made concerned about our absence, and it is a bit of a walk through these twisted delightful Venetian streets, so I think we must take our departure. We have felt greatly honoured by your favoring us with your conversation, Lord Byron, and Mr. and Mrs. Darcy for your hospitality.”

“We have enjoyed it very much,” said Bunny, sincerely, “but do not wish to outstay our welcome.”

“I fear that I have forgotten that you must be very tired from your walk and your visit,” said Mrs. Darcy to the girls. “We would be glad if you would stay to tea, and then we will have our gondolier escort you back, with a servant as chaperone. No question of you walking.”

“Gondolier! Oh! Can I go with the gondolier too?” proposed Lydia, hearing something that interested her for the first time. “You girls are so free! I am a married woman, but my sister and her husband keep me pent up here like a prisoner.”

“Which is what you deserve, I should be very displeased with them if they acted otherwise,” said Lady Catherine tartly.

The visitors gratefully accepted the invitation, and instructions were given to the servants to prepare a fine tea out under the pomegranate tree.

There were several fish dishes, baccala mantecato, a poached cod whipped into a mousse and served with polenta; molesche frite, fried soft-shell crabs; and curled octopus. A delicate calves liver dish, and some veal carpaccio with breads, and some small roasted birds completed the main course; and to finish there was a beautiful Bonet, a custard made with hazelnuts and amoretto, chilled and covered with chocolate glace.

“I do not know,” France exclaimed, regarding the repast, “if it is the ‘done thing’ to speak of one’s fare in company, but this table is so beautiful!”

“It is like a work of art,” Bunny said wonderingly. Lord Byron, however, ate nothing but some biscuits and soda water, and his only reference to the food was to ask, “I am curious, Miss Finkelstein, do you not follow the Hebrew dietary restrictions?”

She sighed. “We did at home, of course, Your Lordship, but it is not possible in this country and while we are traveling. The Burkes are gentiles, and I am not personally devout.”

“I should have supposed not, given your proposed marriage to a gentile poet,” he murmured.

“So when it comes to food, I have ‘to do what the Romans do,’” she explained with a laugh.

“I wish we could provide Jewish foods for Bunny, like matzoh,” France commented.

“Matzoh! You won’t perhaps believe it, but I have eaten that,” Byron said unexpectedly.

“Have you, Byron? What is it?” asked Darcy.

“Why, when I was leaving England, Nathan sent me some matzohs for my journey. He told me how a certain angel assured the safety of a whole nation by providing them with Passover bread, and he wished that the same guardian spirit might accompany me to the lands where I was to sojourn. Very good of him, was it not?”

“I think it is a beautiful story,” said Bunny. “And I am very glad you have eaten matzoh, and know something of my people.”

He bowed, and drank more soda-water, broodingly.

At the end of the meal, the young ladies made their grateful farewells to the denizens of the Palazzo Modenigo, with Lord Byron issuing an invitation to France’s father to come to see him at the next salon meeting if he liked. A servant accompanied them in the gondola to return them safely to their door (Lydia was firmly forbidden a seat), and the others retired to talk over their visitors.

“Very nice girls, upon my word,” observed Darcy, “though it is odd to have entertained two Americans, one of them a Jewess; but they seem a good sort of people.”

“Yes, indeed. Conversible and intelligent, I know I had not read half so much at their age,” said Elizabeth.

“We know all about what your family’s system of education was,” intoned Lady Catherine repressively.

“System!” exclaimed Lord Byron. “I tell you, when a person talks of system, Lady Catherine, his position is usually hopeless.”

She would not contradict his Lordship, and subsided into a prudent silence.

“And may I say that there is nothing wanting in Mrs. Darcy’s education,” he continued. “Or in her kindness in making this visit go off so pleasantly.”

“I wonder if we will see those young ladies again,” wondered Lydia. “I liked that Bunny. I should like to go about with her, we could have fun with the gondoliers.”

Elizabeth raised her eyes to Heaven. “You will not have any opportunity for such a plan of corruption,” she said in a clipped voice.

“Certainly not. They were rather genteel girls, and expressed themselves well,” said Lady Catherine, a tone of surprise in her voice. “Nothing uncouth, even in the Jewess.”

“Yes, they were quite as well educated as me,” said Lydia. “I had thought Americans would be wild Indians.”

“Rrrreally, Mrs. Wickham,” retorted Lady Catherine, contemptuously. “Let me tell you, I have seen many an English young lady with manners and education far inferior to theirs.” She looked expressively at Lydia. “Ignorance is not confined to the American continent.”

“To be sure not, you meet with it everywhere,” laughed Lydia. She reached over to an elegant Roman pot filled with lavender, and broke off a large handful. Elizabeth was about to remonstrate, but Lydia was seized with a violent sneezing fit and wiped her nose on her white muslin dress, which was in fact her sister’s, though Elizabeth, lifting her eyes to heaven in disgust, vowed never to wear it again.

Byron averted his eyes from Lydia, and thoughtfully helped himself to a banana from the fruit bowl. “As you have seen, I generally run from young ladies of the bas blu as from a plague. They are what inspired me to write this verse:

They cannot read–and so don’t lisp in Criticism;

Nor write–and so they don’t affect the Muse;

The would-be Wits, and can’t-be Gentlemen–

I leave them to their daily ‘Tea is ready,’

Smug Coterie, and Literary Lady.

“But these young ladies are something different,” he continued, peeling his banana, “and I should not mind conversing with them again. There was nothing objectionable in them. They had no offensive pride, but proper modesty, and I should like to hear more of what they can tell us about life in America, especially little Miss Finkelstein’s views on her own people.”

“Yes, we know so little of the Jews, and one must be interested,” said Darcy. “I would not have thought to find you such a sympathizer, Lord Byron.”

“I certainly do sympathize with their wrongs, the way they are treated, and as I mentioned, I have known some brilliant men. However I do not pretend to be entirely impartial. When I think of my enormous debts, that contributed to the ruination that sent me out of England, I lay some of the blame on the race of Jewish money-lenders for my sufferings. They are venal enough.”

“Perhaps; but do not forget they are driven to the money-lending, and to desperation, by their treatment in England, being kept from all decent professions.”

“And really, Lord Byron, you ought not blame the mirror if your own face is cracked,” said Elizabeth archly. “We are to blame for our own mismanagement and excesses, if we have them, and not the bank from which we borrowed. Is it not so?”

“Exactly so, my dear Mrs. Darcy,” said Lord Byron with a rueful sigh. “You are always too right.”

“I believe the young ladies said the family was intending a visit of some months here,” said Darcy, consideringly. “Miss Burke’s father would be worth knowing, I think.”

“Yes; I might send a carte of invitation to them for Signora Benzon’s next soiree, and you might come too. I know you hate a salon, however, Mrs. Darcy.”

Palazzo Benzone

Elizabeth laughed. “That was Signora Abrizzi’s. I would not object to trying Signora Benzon’s some time.”

“You would meet some interesting people. There are so many different types in Venice, and they are particularly to be found at the salons. It is as I say:

Masks of all times and nations, Turks and Jews,

And Harlequins and Clowns, with feats gymnastical,

Greeks, Romans, Yankee-doodles, and Hindoos.”

“That sounds like Carnival,” laughed Elizabeth. “A regular ragout of people.”

“But the Benzon salon has the best of literary and artistic society. Canova and Moore go. You live so retired here, you might find it a novel diversion.”

“Canova. Did not Miss Burke say that she wished to be a sculptress?” asked Darcy.

“And a poetess too,” said Elizabeth, smiling. “An aspiring and enthusiastic young lady.”

“She would like to visit Canova’s studio,” said Byron thoughtfully. “It might be arranged.”

“I should like to meet Canova as well,” said Lady Catherine. “Do not forget that I am the greatest great devotee of the sculptural art.”

“Really,” said Lord Byron. “Have you heard what the Empress Josephine has said about his ‘Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker?’ ‘If one could make statues by caressing marble, I would say that this statue was formed by wearing out the marble that surrounded it with caresses and kisses.” He gave a sardonic leer to Lady Catherine, who returned it in kind by fluttering her eyelids terrifyingly. He straightened his face into a sober mask at once.

“You ought to remember, Lord Byron, that despite my undoubted artistic and musical sensibilities, my true forte is as a lady of letters. But you know this from the letters we two have exchanged. It is so important for a young man like you to have a wiser, older correspondent.”

“How can you talk, Aunt Catherine, don’t you know he wants a young woman, like me, someone he can cuddle. What would he want with a dried-up old thing?”

Byron was already on his feet and moving away, as rapidly as he could, despite having a misformed leg that made his progress not as speedy as he clearly wished it could be at this moment. As he went, he turned his glance beseechingly back to Mr. and Mrs. Darcy, and said hastily over his shoulder, “You understand, I must return to my work, and will proffer my thanks and excuses.”

Elizabeth’s laughing eyes met his. “We understand perfectly, Lord Byron,” she said.

14 comments

Skip to comment form

I must admit that I don’t see the attraction to Lord Byron myself! Give me Darcy any day 🥰😉.

I can’t believe how Lydia abuses Elizabeth’s clothes! If I were Elizabeth I would give Lydia a few gowns for herself and tell her she must stick to those regardless, if she dirties them then she must clean them herself and wear them whatever their state! Then I would ensure the doors to my dressing room were kept locked!

Maybe I would also encourage her fascination with gondoliers, maybe she would fall overboard and I doubt if any would be enamoured enough to rescue her! 🤔😂

Oh Glynis, LOL!

Seems you are quite irritated with dearest Lydia! It is a wonder she could put on Elizabeth’s gowns… she was the tallest of her sisters! (insert rolling eyes here)

“If I were Elizabeth I would give Lydia a few gowns for herself and tell her she must stick to those regardless,…”

I admit I thought you were writing: “if I were Elizbeth, I would give Lydia a few” … smacks! She does deserve them… 🙂

😂🤣😂 “smacks” 😂🤣😂 I love it! Maybe one or two for each spoiled piece of clothing? Plus extras for being stupid enough to marry Wickham? Then a few more for abandoning her children? Oh and some more just because! 👊🫲👊🫲😂😂🤣

Author

Glynis – For sure! Imagine getting involved with Lord Byron, the problems! Faithless, undependable, self-centered, horrible treatment of women…On the other hand, he WOULD be entertaining, and was the rock star of his era, but really not worth it! Darcy, on the other hand, is a good AND a clever man. No contest!

I liked the piece of real-life history, the women‘s friendship, and especially Sam’s love and devotion to his partner and her work.

As for the writing challenge, it was not easy but you surely pulled it through!

And Lord Byron is the absolute rock star of the era. The Darcy couple is so lucky to have met him!

Great work and mission completed!

Author

Alexandra, I’m so glad you what I was trying to convey and emphasize: a tribute in so many ways. To women’s friendship, to my mother and her friend, to France and Sam, to the friendship between Sam and myself that developed from Sam’s sharing these discoveries! And you perceive that it really was a tough one, it could have gone “lame” in so many ways, and I got so desperate that I was thinking of making it a time travel story (and I detest time travel stories!). But once I saw the connection through Byron’s Jewish studies, and the fact that the two girls really did read his “Hebrew Melodies,” it clicked into place!

and she was our people as well 🙂

I delighted in the scene – as ever with this story! But the story before the story was very touching as well – don’t we all know people like this ? One minute inseparable, and the next blink you haven’t seen them for a lifetime?

I also appreciated the timing: I’ll have some matzoh tonight thinking maybe Darcy and Elizabeth could have tasted it also… 😉

Happy Pesach!

Author

Mihaela, I was so happy to have used Jewish themes close to my heart in an Austen Variations story. Not easy to work in – putting a girl called Finkelstein into the world of Pride and Prejudice? but once Sam told me that Bunny and France really had read “Hebrew Melodies” together and admired Byron, there was my story! Very warm Pesach wishes to you too. Matzoh all round!

Diana, this was and is absolutely delightful! when will it come out as a complete book?? It will be so captivating.

Author

Hollls, I’m so very happy you enjoyed this! Yes I am indeed working on it as a book, at the moment thinking of calling it The Darcys in Venice, unless I think of a better title…Pride and Palazzos just sounds silly. I am about half through writing but it isn’t a fast job because there’s so much research at every step. Just for this excerpt I had to read Byron and Israel Disraeli, and I’m going to have to read up a lot more on Venetian salon society! (Not that I’m complaining, because I can’t imagine anything that’s more fun!) I hope to have it ready for publication next year.

Hi, Diana. Thank you for sharing this fantastic excerpt. I hope the writing progresses! I’m working on a book about the 1950s and 60s, and in particular the friends and lovers of playwright Lorraine Hansberry. Your mother appears in her archive, as does France Burke. Do you have any stories, letters, diary entries from your mom’s papers about Lorraine Hansberry? Do you know how I can get in touch with Sam Shea? Many thanks! Sara Warner, Cornell University

Hi Sara. Thanks for reading my work, it is continuing to progress! I am fascinated to hear that my mother may have known Lorraine Hansberry, but are you sure the person mentioned is my mother? She was Helen Reeve (nee Finkelstein, nicknamed Bunny), born 1923, died 2014. She and France Burke were close friends at Dalton, and remained in touch for a few years after that, but I never heard that she knew Hansberry. My father, the poet Paul Eaton Reeve, was living in Greenwich Village in the 1950s, and I have his letters; he is more likely than my mother to have met other writers during that period. I’m deeply interested in this aspect of their lives, and would be very grateful if you’d be able to tell me anything more about these references! Or, would the archive be online, so I might search for mentions of my parents?

My father’s mother was the first Asian American novelist, Winnifred Eaton, pen name Onoto Watanna, and I have written her biography (University of Illinois Press, 2001). As a matter of fact there is a centenary conference in Calgary about her later this month, at which I am keynote speaker. I’ll be talking about my father’s work too, and would love to know more about a Lorraine Hansberry connection!

Sam Shea’s email address is greensprite200@gmail.com She tells me that France did know Hansberry, though they weren’t close.

Best,

Diana

I was researching France’s father and fell into the rabbit hole that is the internet. I landed here and am glad I did! Here’s to Bunny and France. Their adventures continue.

Stourley Kracklite, what a delight to receive your comment! I am glad you enjoyed the rabbit hole. My novel The Darcys in Venice has been completed, and I am looking for a publisher. If I can’t find one, I’ll put it on Amazon/Kindle myself. And I’m sure Bunny and France have had their reunion in heaven and are enjoying themselves! Best regards.

Diana