Diana gave us some lovely insight into girl’s education in Jane Austen’s day, (You can find that post HERE.) So now is a good time to look at how gentlemen of the era were educated.

No one really argued for state provided education for middle and upper class children before 1850. (Brown, 2011) So the task was left entirely in the hands of the parents. Although considerable effort and activity went into educating up and coming gentlemen (gentleboys?), it was hardly standardized, depending entirely on the preferences and means of his family.

No one really argued for state provided education for middle and upper class children before 1850. (Brown, 2011) So the task was left entirely in the hands of the parents. Although considerable effort and activity went into educating up and coming gentlemen (gentleboys?), it was hardly standardized, depending entirely on the preferences and means of his family.

Early education

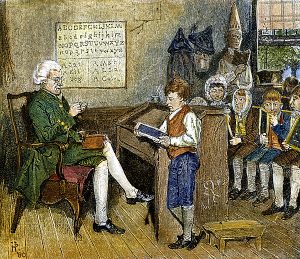

On the whole, early education in the home was preferred. Mothers and governesses would provide a boy’s first education, often teaching him the basics of reading and writing. Usually by the age of seven he would graduate from being taught by women to being educated by men. There were no standards of how this worked though. The specific details varied by family and by social class.

A male tutor might be brought into the home to teach the child, preparing him for the next step in his education. This could continue for just a few years until the boy was deemed ready for a boarding school, or it could continue until he was ready for university study. Alternatively, a boy might be sent to a local scholar, often a clergyman, for lessons as a day student. Many clergymen also took such students on as boarders, running small schools to supplement their income teaching anywhere for half a dozen to two dozen students. The choice of option depended on the education philosophy of the family, usually the father. (Selwyn 2010) This definitely makes me wonder how Darcy’s father would have seen to his education.

A male tutor might be brought into the home to teach the child, preparing him for the next step in his education. This could continue for just a few years until the boy was deemed ready for a boarding school, or it could continue until he was ready for university study. Alternatively, a boy might be sent to a local scholar, often a clergyman, for lessons as a day student. Many clergymen also took such students on as boarders, running small schools to supplement their income teaching anywhere for half a dozen to two dozen students. The choice of option depended on the education philosophy of the family, usually the father. (Selwyn 2010) This definitely makes me wonder how Darcy’s father would have seen to his education.

Preparatory Schools

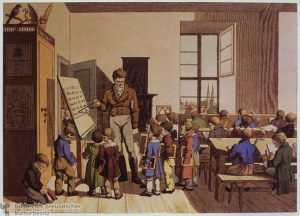

These smaller schools ,which routinely took boys in the 7 to 13 year old age range, were often referred to as preparatory schools. The prepared boys for the larger public schools that often preceded entry into the universities.

These schools were usually held in the schoolmaster’s home. Jane Austen’s father, Rev. George Austen conducted such a school out of the vicarage in Steventon. His living as a vicar was £230 a year. He charged £35 per term for each of his student boarders. It is easy to see how taking even just a few students could substantially augment his family’s income. The work though did not fall on him alone. His wife cooked, cleaned, sewed, and mother-henned the boys in her care, much like a surrogate mother. (Sanborrn, 2016) (If you are reading “A Chance Meeting’, you’ll get a peek at this wort of school. You can find the story HERE.)

Die Unterrichtung der Knaben an einer städtischen Schule der Biedermeierzeit; Radierung von Johann Michael Voltz, 1823

Original: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kunstbibliothek / Lipp Dd 5

Standort bitte unbedingt angeben!;

By modern standards, preparatory school curriculum was very limited. It consisted mainly of Latin and Greek classical texts (both prose and verse), modern and ancient history, some mathematics, and the use of globes to locate nations. French and Italian might be taught as extras (for additional fees), along with handwriting, dancing, drawing and a smattering of scientific subjects. (Le Faye, 2002) No standards existed, so there was no guarantee that a particular teacher was actually well versed in the subjects he taught but since teachers were most often clergymen or failed ordinals, there was reason to hope that they were at least educated themselves.

After their education in these preparatory schools, boys might then progress to a public school.

Public Schools

Public schools were public in the sense that boys were taught in groups outside of their private homes, not in the sense that these institutions were funded by public funds. A number of public schools existed, but the landed elite (like the Darcys) usually chose to send their sons to a select number of these schools: Eton, Harrow, Winchester, Westminster, Rugby, Charterhouse and Shrewsbury. (Adkins, 2013)

The exact timing and duration of a boy’s stay at school varied. Some were sent as young as age seven and stayed until age eighteen. More commonly boys started public schools around age thirteen and stayed about five years. The boys’ lives at school differed significantly from modern schooling in two major ways: the curriculum taught and the life style of the students.

The exact timing and duration of a boy’s stay at school varied. Some were sent as young as age seven and stayed until age eighteen. More commonly boys started public schools around age thirteen and stayed about five years. The boys’ lives at school differed significantly from modern schooling in two major ways: the curriculum taught and the life style of the students.

What was Taught

Students were expected to know some Latin upon arrival to public school. “The first two years of their education was entirely a study of Latin–memorizing, reciting, reading, and answering set questions in that language.… Thus they learned to be confident public speakers, first in Latin, then in classical Greek and finally in English.” (Bennetts 2010) These studies also developed an understanding of the moral and philosophical issues brought up by the classical thinkers and a literary appreciation of poetry and prose. Dancing, fencing and other sports also featured in some curriculums.

What was notably absent from both public school and university educations were courses on anything the modern mind would consider practical. Since these establishments catered to gentlemen who were not destined to actually work for their living, courses like bookkeeping or land management that might equip them for jobs (oh the horror!) were relegated to schools that catered to the sons of men in trade. (Selwyn 2010)

This really says something about Mr. Darcy if you think about. All the knowledge he would have needed to be an excellent master of Pemberley—which Mrs. Reynolds assures us he was—he would have to acquire through his own dedicated study. That he would have taken the time and effort to educate himself on these matters tells us a lot about his character.

Life in public school

Once they entered public school, most boys spent the majority of their year at school, with only a few weeks of holidays spent back at home during the year. They either boarded at the school itself or in town at boarding houses known as ‘Dame’s Houses’ usually overseen by a ‘Dame’ or landlady. In the early 1800s, about thirteen such houses were associated with Eton. Although school life was very regimented, with school days running from six in the morning until eight in the evening, there was very little direct supervision over the boys. They were often left to fend for themselves.

Once they entered public school, most boys spent the majority of their year at school, with only a few weeks of holidays spent back at home during the year. They either boarded at the school itself or in town at boarding houses known as ‘Dame’s Houses’ usually overseen by a ‘Dame’ or landlady. In the early 1800s, about thirteen such houses were associated with Eton. Although school life was very regimented, with school days running from six in the morning until eight in the evening, there was very little direct supervision over the boys. They were often left to fend for themselves.

With a strong economic incentive to admit as many students as possible, public schools were often so crowded that even beds were shared by two or more boys at the same time. Those same incentives also influenced the quantity and quality of food made available to the students. Those with pocket money frequently supplemented their rations at local shops. (Brander, 1973)

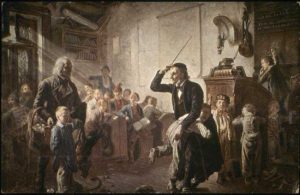

Almost no limits were placed to the amount the boys could drink, gamble, fight and indulge any sexual bent with maid servants, local prostitutes, and girls living in town. Even the institution of prefects (older boys in charge of younger ones) did little to curb the out of control behavior. “ … Most schools suffered occasional rebellions, or mutinies, resulting in mass expulsions or floggings. In 1797, Dr. Ingles, headmaster of Rugby, had his door blown open by gunpowder. The boys at Harrow were even more ambitious, setting up a road block and blowing up one of the governor’s carriage.” (Brander, 1973)

Bullying and Brutality

Not only was dissolute, licentious behavior the norm, bullying and brutality were expected. Corporal punishment consisting of flogging with a birch, or caning with a rod until blood was drawn from the bare buttocks, was regarded as the normal and accepted punishment for transgressions. Such punishments were frequently delivered in public, adding additional humiliation to the experience.

Not only was brutality dished out from the masters to the students, older boys were put in charge of younger ones and permitted to order them about and punish them with beatings just as the school masters did. Depending on the sorts of friends a boy did or did not make and how he got on with others, especially older students, a boy’s public school years could be very testing indeed. It is interesting to think about how Darcy might have coped in the public school environment.

Not only was brutality dished out from the masters to the students, older boys were put in charge of younger ones and permitted to order them about and punish them with beatings just as the school masters did. Depending on the sorts of friends a boy did or did not make and how he got on with others, especially older students, a boy’s public school years could be very testing indeed. It is interesting to think about how Darcy might have coped in the public school environment.

Why was it tolerated?

If public schools could be so bad, why did not parents intervene? Why would a father who had suffered through such school days send his son into a place that brutalized him?

In short, such an environment was regarded as essential for inculcating the toughness and fortitude men needed to perform their social roles. “Educators and parents subscribed to the principle that one was fit to command only after one had learned to obey. And those young boys of the gentry and nobility were there to learn their place and destiny in England’s highly structured society.” (Laudermilk, 1989)

So, even if a boy had been able to appeal to parents for help, he would have been unlikely to receive either assistance or sympathy. At a very tender age, he was literally on his own, to survive the experience in whatever way he could. Is it any wonder that the friends a boy made during his time in public school were often strong allies for a lifetime? Darcy and Bingley’s friendship makes a great deal more sense in light of this, doesn’t it?

3 comments

What an interesting, informative piece – I’m so glad you contributed to “Jane Austen and School” month, Maria Grace! Now I’ve been wondering about something. Jane Austen never tells us how Darcy and Bingley met, and I’ve often wondered if they were school friends. However, Darcy at 28 is several years older than Bingley, who is 23. But it’s the right age difference for Bingley to have been Darcy’s “fag” at school – not a sexual reference, but as you say, the older boys were in charge of the younger ones!

Wow, I love those pictures of the various depictions of school life. In the 80s movie version of Sense and Sensibility, Sir John Middleton stated he could hardly wait until his son went to Eaton [I think], where they would thrash him black and blue. I guess he felt his son was overindulged and smothered by his overprotective mother. Sir John was rather smug about the whole thing. When he was introduced to Edward Farras, he referenced connections through school with a relation. As you stated, schoolmates established a network of connections that helped or hindered future endeavors and relationships for a lifetime. This was very interesting.

I am so grateful for the time and energy you dedicate to your research. Your posts are always so informative and interesting!

~Anngela Schroeder